The greatest soccer player of all time arrived in Florida midsummer and hit this league of ours like a thunderbolt.

If you’re reading this column, I’m sure you already know that. But let’s travel back a month and a half to appreciate what Lionel Messi has done for Inter Miami CF anyway:

- Banged home a free-kick at the death to give the Herons a 2-1 win over Cruz Azul.

- Scored a 22-minute brace, then set up a third in a 4-0 rout of Atlanta.

- Introduced himself to the neighbors with another brace – and a yellow card! – in a chippy 3-1 win over Orlando.

- Another brace, which included another late free kick, in a 4-4 draw at Dallas that Miami eventually won in a PK shootout.

- Tapped home the final goal in a 4-0 destruction of Charlotte to advance to the Leagues Cup semis.

- Caught Andre Blake cheating off his line for Miami’s second goal, which proved to be the decider in a 4-1 win at Philly.

- Hit a wonder goal with what was his only even half-decent look of the night in the final (and in the history of our sport, Messi is the only player for whom that look would qualify as even “half-decent”), which Inter would go on to win in penalties. First trophy in club history secured.

- Four days later, led Miami to an improbable comeback in Cincinnati with two inch-perfect assists in a 3-3 draw, which led to another PK shootout win, which put Miami 90 minutes away from a second trophy in club history.

- Came off the bench three days after that in Harrison and iced the cake with a gorgeous team goal in a 2-0 win with massive playoff implications.

- Notched two more assists in Miami’s 3-1 statement win in downtown LA on Sunday night.

“Amazing” isn’t a strong enough word. I’ve been watching this league for 28 years and I’ve never seen anything remotely like what Messi has done (apologies to Nico Lodeiro, Didier Drogba, Hristo Stoichkov and Jaime Moreno). He, along with a host of new teammates and new head coach Tata Martino, got off a plane and immediately elevated this Miami team to magical heights.

In the process he also, the narrative has gone in some quarters, exposed the league’s defenders, laying bare their incompetence. And if you just watched the Atlanta game, then fair enough – nobody would mistake what the Five Stripes presented on the day for defensive competence. Although I would point out the first goal Atlanta conceded to Messi is almost the exact same goal they conceded to Bernard Kamungo on Saturday: a direct run onto a ball over the top because Atlanta play a suicide line with no pressure on opposing CBs or d-mids. They conceded this goal multiple times before the Leagues Cup as well. It doesn’t take the GOAT to expose that.

Or if you just watched the Philly game, you’d say he was exposing MLS goalkeepers. And yeah, Blake had himself a shocker in that one, choosing the worst time to have his worst game in years (maybe ever). But also, nobody arguing in good faith judges a player, let alone an entire league, upon one outlier of a bad performance. When it comes to Blake in particular we have plenty of data over the past decade that says he’s basically the same level of goalkeeper as Matt Turner, and fractionally behind Djordje Petrovic.

Those guys are Premier League goalkeepers. If you think Premier League goalkeepers don’t make the occasional error, then you don’t watch the Premier League, because nightmares like the one Blake had last month happen to somebody every single weekend in the consensus best league in the world. That’s the way the sport goes.

This is also the way the sport goes:

“Sometimes ball go in” is not as satisfying a narrative as “Messi is laying bare MLS shortcomings,” so what analysis I’ve seen has been pretty heavily skewed towards that second take. And look, I get it, because there are definitely moments when shortcomings in certain MLS teams have, in fact, been laid bare by Messi’s singular genius (RBNY backline, welcome to hell).

But also, sometimes ball go in. Sometimes not. Even for Messi.

Overall, what’s been so stunning to me over his first month-and-a-half wearing pink is Messi’s been able to come here and basically play his greatest hits. There are the free kick goals, which we’ve seen dozens of times in Europe and with Argentina, and then there are the times he’s able to drift to the back post off of his center forward’s gravity, which we’ve seen dozens of times in Europe and with Argentina. And of course, there’s the “hit a long diagonal to Jordi Alba on the overlap then race to the penalty spot to one-time the pullback,” and god look at how awful these MLS defenders are.

In other words, the Messi we’ve seen in MLS thus far is the Messi we’ve seen everywhere else he’s played for the past 10 years, laying bare the shortcomings of opposing defenders and goalkeepers the exact same ways he’s always done. And the underlying numbers agree: Through 11 games for Inter Miami he’s at 10.08 combined non-penalty xG+xA, as per TruMedia via StatsPerform. That’s roughly in line with the numbers from his final six seasons in Europe, in which he put up 177.9 combined npxG+xA in his 196 league appearances, as per FBRef.

Naturally he is overperforming those underlying numbers here, with 11g/5a so far (only counting primary assists).

That said, he overperformed his numbers in Ligue 1 and LaLiga as well. In those final six seasons he put up 232 combined goals + assists, an overperformance that isn’t quite as large as what we’ve seen thus far with Miami. But as I’ve said for the past few weeks any time someone’s shoved a mic in my face: the man’s been on one, and even Messi eventually regresses toward the mean, if not exactly to it (just one goal in his past four games, for what it’s worth).

I have taken a very scenic route to my point, which is this: The arrival of Messi, Alba, Sergio Busquets et al has sparked off another debate about MLS’s standing in the global hierarchy of leagues, a topic I truly hate. I hate it because no one has perfect, or even unbiased knowledge about any league, let alone every league*. Moreover, there is no perfect data set to compare clubs and leagues across regions, or even within regions.

(*) My perfectly unbiased take is Herc’s right about this one…

Case in point: Remember, up above, where I said the EPL is the consensus best league in the world? Loathe as I am to admit it, that is also my assessment. However, across the three major continental competitions last year (the UEFA Champions League, Europa League, and Conference League), Italy's Serie A produced as many semifinalists (five) as the other Big 5 leagues combined. That seems a pretty great argument for that particular league’s strength and depth!

But it doesn’t really work that way, because everyone who matters understands small sample size results are an imperfect measure that can be skewed by variance and vibes. Sometimes ball go in. Sometimes not.

Imperfect measures, however, are all we have, and after 1,200 words of preamble it’s time for me to plant my flag. Here’s where I’ll plant it: Messi’s performance in MLS thus far is another soft data point that suggests this is a top 10 league and rising. He’s dominating individually slightly more than he did in France with a dysfunctional PSG side, and slightly less than he did in Spain with a mostly functional Barcelona over his final five years there. His MLS performance is also in line with the dominance he showed over the course of the last cycle of Conmebol World Cup qualifiers with Argentina, and then into the World Cup itself.

But we have more to go on than just what Messi’s done. We have international call-ups, and the global transfer market’s assessment of MLS in its current state, and even, yes, Transfermarkt valuations.

Imperfect measures, all. But let’s peel back some layers of this onion and see what we can see anyway:

Thus far there are 66 call-ups for the September 2023 window, per the MLSsoccer.com tracker, with somewhere from five to eight more expected to be announced in the coming days. Note there are only four MLS players called in for the USMNT, though there are 15 total players in the US roster who either played in MLS or came through MLS academies and were then sold on to European teams. And there are no call-ups for Canada this window since the CanMNT weren’t able to get games on the docket (yikes).

Go back to September 2015 and there were 55 MLS players called into that September window, with 22 combined coming from the US and Canada. Of those 22, only one of the Americans and eight of the Canadians had MLS academy backgrounds. It was a completely different era.

Fast forward to 2019 and you get a September window with more than 90 MLS players called in, and again it’s the USMNT and CanMNT leading the way, with 12 and 17 MLS-based players, respectively. This time 15 of those 29 had MLS academy backgrounds.

The bigger difference, however, is where the rest of those call-ups came from:

- 2015: Seven players total from Conmebol and UEFA nations (Kaká, Robbie Keane and Sebastian Giovinco being some names you’d recognize).

- 2019: 34 players total from Conmebol and UEFA nations (Peru with five, Venezuela and Finland with four each being the best represented)

- 2023: 39 players total from Conmebol and UEFA nations so far (Eight Venezuelans, six Peruvians, four Paraguayans)

I think the data is telling the truth here: explosive growth from 2015 to 2019 (this coincided with the introduction of the third DP as well as TAM), followed by more measured growth since then (the U22 Initiative being the one big roster change). Note that in general, though, the UEFA and Conmebol players from the current rosters play for better countries than the ones from 2019. Luxembourg and Liechtenstein have been replaced by Ukraine and Switzerland, while the Chilean trio of José Bizama, Felipe Gutiérrez and Diego Rubio from 2019 have been replaced by the Argentinean trio of Messi, Thiago Almada and Alan Velasco in 2023.

Of all the players in all the camps across all of MLS history, Messi is the most important call-up. This is the first time the reigning best player in the world has been playing in this league, and his presence alone is a data point in MLS’s favor as, to use a phrase often heard ‘round these parts, a league of choice.

Almada might be No. 2 on that list, because he was one of 35 MLS players at the World Cup – most of any league outside the Big 5 – and was the first active MLS player to actually win a World Cup. MLS also had the sixth-most players active in the knockout rounds of the World Cup, which seems to be another valuable data point.

There is an argument to be made Velasco is No. 3 on that list. Unlike Almada, Velasco came here as a teenager and played his way into the senior Argentina set-up with his MLS performances. It is the first time I can remember MLS playing a significant role in developing a player for one of the truly top national teams (Maybe Noel Buck will be the second!).

It is an exciting and potentially groundbreaking development, one that should herald a new era. Only time will tell if that will ultimately be the case, but I am bullish.

Why? Because MLS teams have already developed other players, myriad and sundry. The top club teams in the world have noticed.

No one should ever assume markets are completely rational, but on balance, I think we can agree the biggest teams do their level best to try to buy the best talent, and the places they shop for that talent tend to either be reliable producers of high-end talent (think Sporting CP), or great weigh stations on the road to the very best teams in the world (Benfica), or both (Porto).

MLS, collectively, was reluctant to sit down at this particular poker table until about 2018, and didn’t start playing big boy hands, really, until 2021. With the summer transfer window now mostly closed (it’s still open in Turkey and a couple of other spots, but I didn’t feel like pushing this column back a week), now’s a good time to see what the league’s collective stake is. All data below is per Transfermarkt:

Since 2020, which means across the last eight transfer windows, MLS is eighth in total expenditure (behind the Big 5 leagues, Portugal and Russia) and 19th in total income (behind the top two flights in each of the Big 5 countries, as well as the top divisions in Portugal, the Netherlands, Brazil, Belgium, Argentina, Austria, Russia and Turkey).

Since 2021 – across the last six transfer windows – MLS is again eighth in total expenditure behind the same collection of leagues as above. MLS climbs to 14th in total income from player sales, though, leapfrogging all the second divisions except for the Championship, as well as the Turkish top flight.

Across the past four windows, dating to the start of 2022, MLS is (you guessed it) eighth in total expenditures and drops one spot to 15th in total sales. The reality, though, is the group from 12th through 15th all did between 208m and 234m in player sales, while 8th through 11th did between 386m and 442m, 5th through 7th did between 667m and 865m, while the top four leagues in player sales were between 1.1b and 1.8b. As always, I tend to think of things in tiers.

Also note in several of these leagues (The Eredivisie, Portugal’s top flight, Argentina, Austria, Denmark, Turkey), the vast majority of player sales revenue is generated by a bare handful of teams. In MLS it’s more diffuse.

The other massively confounding factor in all of this is zero MLS teams need to sell to survive. My assumption is this lowers the total volume of outgoing MLS deals, as does the fact MLS players are well-paid (per publicly available info, MLS players are on average the sixth-best paid in the world, behind only the Big 5 leagues).

One more note, for comparison’s sake: In the final eight transfer windows of the 2010s, MLS was 16th in total expenditures and 32nd in total revenues from player sales. Narrow it down to the final six windows and you get… 16th and 31st. Over the final four windows it’s 16th and 24th – things really started moving with the sales of Miguel Almirón, Alphonso Davies and Tyler Adams in late 2018/early 2019.

Ok, so we know MLS teams are buying more and selling more, and those players are going on to represent some of the best national teams in the world, and players who are neither bought nor sold (Messi, Busquets et al) are now, more often, choosing to ply their trades here. But is there anything beyond that and salaries and the eye test and what little head-to-head data exists to determine how good, actually, this thing of ours is compared to what exists overseas or across the border?

Enter Transfermarkt once again. I’ll borrow a line from _The Athletic_’s John Muller here: [their] crowdsourced numbers can serve as a decent stand-in for the overall quality of a squad. I would add there’s a strong element of age-weighting to their values (even Phil Foden’s mom doesn’t think he’s 3x the player Messi is), but on balance, the website’s a really useful tool for this particular exercise.

Here is every relevant league’s median club value and average club value:

1. English Premier League

Median: 392,000,000

Average: 527,500,000

2. German Bundesliga

Median: 167,000,000

Average: 221,111,111

3. Italian Serie A

Median: 165,000,000

Average: 230,000,000

4. Spanish LaLiga

Median: 132,000,000

Average: 235,000,000

5. French Ligue 1

Median: 106,500,000

Average: 195,555,555

6. Brazilian Série A

Median: 69,900,000

Average: 72,000,000

7. English Championship

Median: 53,770,000

Average: 70,833,333

8. Major League Soccer

Median: 43,250,000

Average: 44,137,931

9. Liga MX

Median: 36,150,000

Average: 45,105,555

10. Belgian Jupiler Pro League

Median: 32,400,000

Average: 49,221,875

11. Turkish Süper Lig

Median: 31,700,000

Average: 53,500,000

12. Russian Premier Liga

Median: 29,600,000

Average: 50,108,125

13. Dutch Eredivisie

Median: 25,750,000

Average: 54,332,222

14. Argentine Liga Professional de Futbol

Median: 23,850,000

Average: 28,492,500

15. Liga Portugal

Median: 20,000,000

Average: 70,555,555

You can see the difference between the median MLS roster value and the mean roster value is the smallest in this data set. So is the delta between the least-valuable MLS roster, as per Transfermarkt’s numbers (CF Montréal), and the most (Inter Miami… duh). In addition, every league in the world – save for the Big 5 – has multiple clubs with assessed values lower than Montréal’s. In the case of Portugal and the Netherlands, it’s two-thirds of the league below that mark. In the case of Russia, Turkey and Belgium, it’s nearly half.

Benfica, Ajax and Galatasaray, in other words, do a lot of heavy lifting for the perception of those particular leagues (to be fair they do all of it, as anyone who’s suffered through Boavista vs. Vizela will attest), and MLS doesn’t yet have clubs like that. And honestly, not having clubs like that has been kind of the point all along: parity is built into the model.

That means you can can take a stab at predicting MLS (I had Cincy as the Supporters’ Shield winners entering the season and feel really smug and good about that pick), but more often than not you will fail miserably (in the 2022 preseason I, uh, predicted Atlanta would win MLS Cup). The higher floor and lower ceiling make for a greater number of competitive, interesting and unpredictable games compared to virtually every European league.

I think more competitive games are better. But also, I’m a big fat hypocrite because I never enjoyed soccer more than when Messi was at his absolute apex at Barcelona, first under Pep Guardiola and then Luis Enrique. When that team took the field, we knew the result before a ball was kicked in anger about 90% of the time, and I wasn’t in it for the competitive balance.

So I completely understand the fans and pundits who are calling for less parity and more SuperClubs.

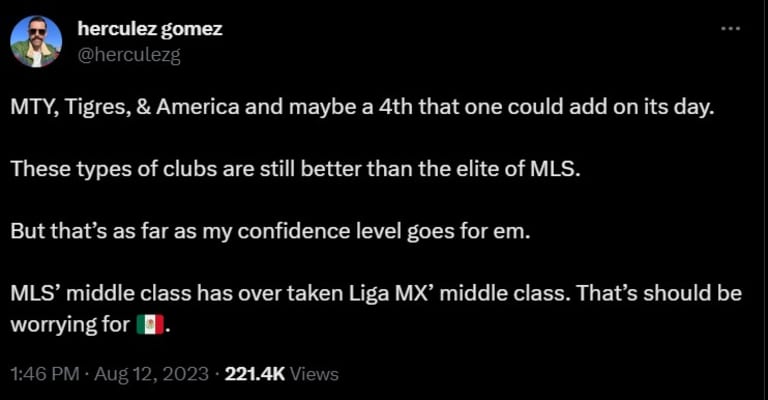

Where does that leave us, then? About where I had assumed it would upon embarking upon this project: MLS has a few good arguments for being just inside the top 10 leagues in the world, and there are a few other good arguments that it’s merely knocking on the door and not there quite yet.

Wherever you land, though, what’s clear is the league seems poised to enter a new era. The U22 Initiative has brought more talent and Messi has brought more eyes, and those two things in conjunction tend to mean more shopping and buying and investments, both incoming and outgoing. Imperfect measures all, but taken together that means better players, better teams and a better league.

For me, anyway, that’s the truth Messi’s arrival laid bare this summer. Now it’s up to Inter Miami and 28 other teams to just keep climbing the ladder.