When the 2016 AT&T MLS All-Star Game kicks off on Thursday, June 28 at Avaya Stadium (7:30 pm ET, ESPN, UniMás, TSN), the world will bear witness as many of the top names in international soccer face off when the MLS All-Stars meet Premier League side Arsenal.

The 2015 opening of the venue, the shiny home of the San Jose Earthquakes, represented a high-water mark for soccer in the Bay Area. But unbeknownst to many followers of the beautiful game, the history of the pro game in San Jose stretches back much further — about four decades.

A sleepy city an hour’s drive south of San Francisco, San Jose in the early 1970s boasted roots in agriculture, not in soccer culture. But that would all change in 1974 when Milan Mandaric, a technology pioneer in the days before Silicon Valley, purchased a franchise in the first iteration of the NASL. He announced they would play in his adopted hometown — and thus, the team that would become today’s San Jose Earthquakes was born.

“Back in the early 1970s, there was nothing to do here,” recalls Gary Singh, a San Jose native and author of The San Jose Earthquakes: A Seismic Soccer Legacy. “San Jose was the definition of a suburban wasteland, and there had never been anything like professional sports in our city.”

Singh played youth soccer back in those days, but the idea that a pro league with pro players was even a possibility presented an awakening in the city.

“Suddenly this new team shows up, and they are all over the place,” he says. “They are making appearances in shopping malls, they’re coming to our practices, they’re doing lectures, and they’re even coming to the houses of fans for dinner.”

The NASL took the town by storm, and by the summer of 1974, the Quakes’ inaugural season, fans flocked to Spartan Stadium in numbers that instantly set league records. Players on that team connected quickly with the rapidly growing fan base. Leading scorer Paul Child and fiery midfielder Johnny Moore became household names for South Bay soccer lovers, and the sport transformed San Jose.

“What a beautiful place it was,” recalls Chris Dangerfield, a Portland Timber in 1974 and later on an Earthquake. “Back then, there were a lot more orchids, and open space — plenty of green grass, too — but most of all, it was a vibrant soccer community.”

Dangerfield moved to the US from England as part of the wave of soccer talent that stocked those early NASL teams. He eventually settled in San Jose when his professional career ended in the 1980s and today, he’s a television broadcaster for the Earthquakes. It was in those early years that he learned he had a bigger role to play than the one on the field.

“We would go out into the community on a daily basis and sell the game,” he says. “Their play really enthused the fanbase, and it created the platform, the stage for what soccer would become in San Jose.”

Singh echoes these sentiments. “It was guerilla marketing,” he says, “even before that term was ever invented.”

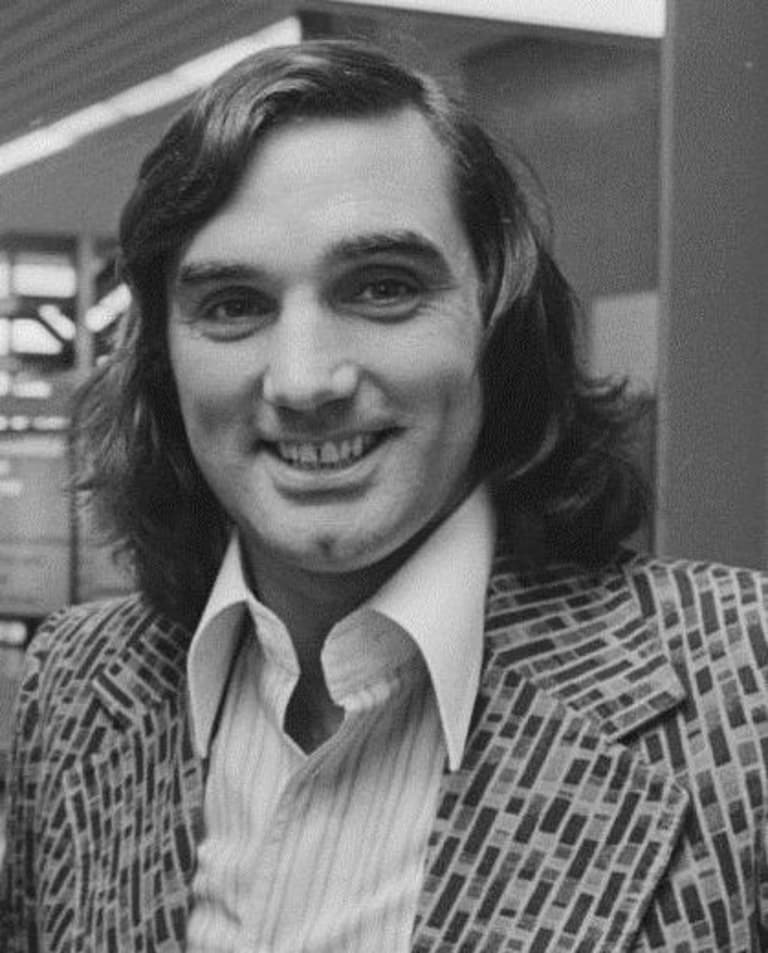

The halcyon days of the NASL, the years when superstars such as Pelé and George Best plied their trade in the US, saw San Jose rally around its team. (Best himself would play for the Earthquakes in the early 1980s.) Spartan Stadium would prove the epicenter of it all.

Legend George Best played for the Earthquakes in the early 1980s. Image CC by 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The city was always more of a commuter town, so match days at Spartan provided a gathering spot for soccer fans far and wide, and everyone there knew everyone else. Even the players got involved.

“Our social lives revolved around the team,” says Dangerfield. “Back in the those days, we’d meet with friends and families before the games at the tailgates, and we’d stop and say hello to all the fans on our way into the stadium.

“After the games, there’d always be a party where the fans would mob their way in, and it would be a great night for everyone involved.”

Legendary downtown hangout Lou’s Village would then serve the post-game crowds, with the festivities carrying on into the wee hours. It was a great time to be a player and a fan, and the good times looked certain to roll on.

But then, the original NASL faltered, and by the mid-1980s, it was gone. The Earthquakes persisted for a few more seasons, surviving on the revenue generated from the big international club friendlies then-owner Peter Bridgewater organized at Spartan Stadium. Then they, too disbanded, and San Jose’s first professional sports team was no longer.

The spotlight on the game may have temporarily gone dark, but throughout San Jose, soccer continued to survive in the expanding ranks of youth players and the resilient amateur teams that dotted the area. Fans moved their gatherings to the Britannia Arms, south of downtown, and kept alive the idea that professional soccer could be resurrected. San Jose would not have to wait long for the stars to return.

In 1989 Bay Area real estate attorney Dan Van Voorhis founded the San Francisco Bay Blackhawks, a team that featured a litany of local soccer talent during its five-year run. John Doyle, Dominic Kinnear, Troy Dayak, Eric Wynalda, Paul Bravo, Marcelo Balboa — all would get their start with the Blackhawks, long before they became household names for the US men’s national team and eventually MLS.

“I remember as a youth player getting to play at half-time during a Blackhawks game at Spartan Stadium,” says Joe Cannon, who would go on to play seven seasons with his hometown Earthquakes. “I knew then that I wanted to play soccer. It was such a rush to be on that field."

The Blackhawks made an impression on the next generation of San Jose soccer stars, and Cannon says now, “I felt as a young kid that it was always my destiny to play in San Jose.”

He attended Santa Clara University and played college soccer at Buck Shaw Stadium — the same stadium the Earthquakes would later call home from 2008 to 2014. And with the advent of MLS in 1996, and a team then called the San Jose Clash, Cannon now had the opportunity to become a professional soccer player in his hometown.

Given the passionate local fan base, it was no accident that San Jose was chosen to host the inaugural game of Major League Soccer, with Spartan Stadium providing the perfect venue for the occasion. Fans from around the Bay Area, including future Earthquakes superstar Chris Wondolowski, filled the bowl for the match against D.C. United.

They all cheered enthusiastically when Wynalda scored in the 88th minute to give the Clash a dramatic 1-0 victory. Soccer was back in San Jose, and the magic of the day made an impression on everyone in attendance.

“Even though I was a kid, I remember the inaugural game well,” says Ted Ramey, son of storied Bay Area sportscaster Hal Ramey, and the current radio voice of the Earthquakes. “They gave out these T-shirts, and the next day I saw kids in my neighborhood wearing them. It was like a rallying point for talking about the game.”

The San Jose Clash hosted D.C. United in the first-ever MLS game in 1996. Photo via Tony Quinn

The younger Ramey would attend many games at Spartan Stadium, helping his dad on the broadcasts and learning the craft of calling a soccer match from a man who served as the voice of the NASL Earthquakes back in the mid-1970s. “It was very cool to follow in that tradition and become a part of the club and the community,” he remembers.

MLS firmly took hold in San Jose following a couple of tumultuous seasons. Soon after Cannon joined the team as a rookie in 1999, the team rebranded as the Earthquakes and went on to capture MLS Cup championships in 2001 and 2003. Landon Donovan, Jeff Agoos, Dwayne De Rosario — the Quakes were definitely stacked in those years, and it was still a team whose ethos resonated with the fan base.

“The Earthquakes always played with a chip on their shoulders,” Cannon says. “That hard-working mentality is something the community really embraced. The local guys really felt the connection and we were even more invested in making strong ties with the fans.”

One such fan was Steven Beitashour, a rising youth talent who was a regular at Spartan Stadium from the beginning of MLS. He had even regularly volunteered to work on game days in his quest to make it on the field. An unheralded rookie in 2010, Beitashour rose to prominence with his hometown Quakes, and in 2012 was named an MLS All-Star. Today a player for Toronto FC, he credits the support of friends and family in the community as helping him succeed as a professional.

“Growing up here, I was a fan of the Quakes first; then I was a ball boy on the field, so I know how passionate and supportive the fans can be,” he says.

The ties to the community also run deep for Beitashour’s fellow 2012 MLS All-Star teammate, Wondolowski, who was almost an afterthought draft pick by the Quakes in 2005. Wondolowski spent three-and-a-half years with the Houston Dynamo, after the Earthquakes moved there and rebranded following the 2005 season. But he was traded back to San Jose shortly after the Earthquakes returned to MLS in 2008 following a two-year hiatus.

Chris Wondolowski at work for the Quakes at Buck Shaw Stadium in 2010. Photo via USA Today Sports Images

“Wondo,” as he’s better known, has never looked back, rewriting the club's record book in the process. A student of the game and its place in the local community, Wondolowski is never at a loss for a good soccer conversation when he is out on the town.

“That’s what I love about San Jose,” he says. “Interest in the game has continued to grow exponentially, and it’s amazing to see the youth and club soccer scene grow along with it.”

He feels it when he’s at appearances at schools and businesses throughout the city, and other times, he feels it, say, when he swings by Ike’s Sandwiches for the eponymous “Chris Wondolowski.” (It’s a spicy concoction of avocado, habanero, provolone, salami, and turkey.) His connections to the San Jose Ultras supporters’ group make him an even bigger favorite of Quakes fans, and they treat him like soccer royalty.

“I get recognized all the time when I am out,” he says, “and the interactions have been so positive almost everywhere I go. I’ve always been so proud of our fans. They are always so knowledgeable and passionate.”

And now, since last year, they have Avaya Stadium to call home. More modern than Spartan Stadium, more fan-friendly than Buck Shaw Stadium, it’s the new gathering place for the San Jose soccer community. From the line of food trucks providing all types of cuisine, to fans on the lawn, to the TCL 4K scoreboard bar supplying their refreshments, the venue is the launching point for the future of soccer in San Jose.

“They were a homeless team for 40 years,” says Singh of the Quakes, “but not anymore.”

Cannon sees a future brighter than ever for San Jose soccer. “So many people have brought us to this moment, and for the Earthquakes, things will certainly evolve over time,” he says. “But there are many more chapters in this story to write. I am very excited to see how this grows.”