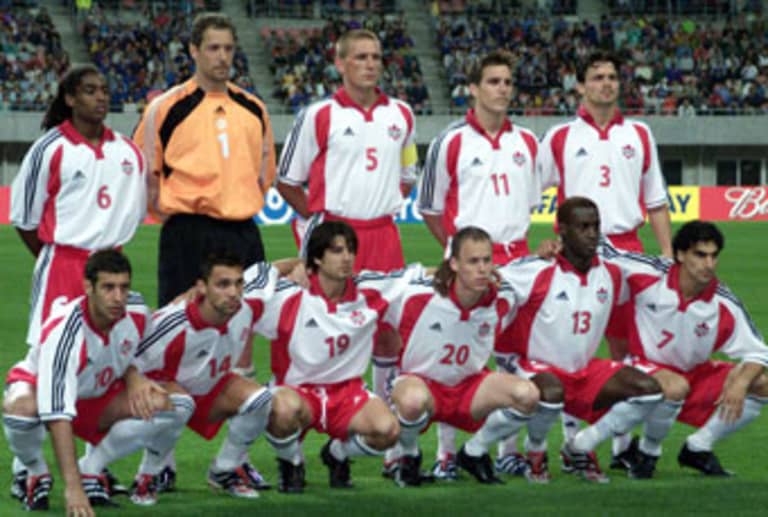

Fifteen years ago, the Canadian men’s national team achieved one of their greatest triumphs, unexpectedly emerging as CONCACAF Gold Cup champions.

But ask any Canadian – aside from the hardest of hardcore soccer supporters – about that 2000 tournament today, and you’re likely to be met with a blank stare. Perhaps it's the passage of time. Or, more likely, it's because Canada largely failed to build on that historic moment.

Underdogs from the start – captain Jason DeVos, who scored the game-winning goal in the final against Colombia, threw the pre-tournament press guide in the garbage after reading that his team "basically had no chance of advancing" – Canada survived via coin flip and golden goal before dispatching Colombia to make history at a soggy, mostly-empty LA Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles.

For the players, who’d achieved Canada’s greatest soccer triumph since qualifying for the 1986 World Cup, it felt like the start of something special.

“There was a lot of belief at that time,” says Mark Watson, who scored the winner against Trinidad & Tobago in the semifinals. “There was a lot of optimism and a lot of confidence once we did win [the Gold Cup].”

Yet 15 years later, few Canadians know about the result. Perhaps it was a lack of media coverage. Or maybe it was difficult for fans to connect with a team that mostly played overseas. It also didn’t help that MLS, still in its infancy, was seven years away from adding a Canadian team.

But above all, the players say, it came down to the team’s inability to build on that momentum and perform well in World Cup qualifying.

“Everything kind of revolves around the World Cup,” says Watson. “If you qualify, it’s a big event and everything else pales in comparison.”

Just months after the Gold Cup win, Canada crashed out of qualifying for the 2002 World Cup. They have not made it to the final round of qualifying in any of the four cycles since. An encouraging run to the semifinals of the Gold Cup in 2007 (the same year MLS welcomed its first Canadian team, Toronto FC) provided a slight uptick in attention – but, once again, it didn’t last.

“Even getting to that stage and getting so close to a final, that didn’t really pick up steam for the program,” says Martin Nash, who was playing in his last Gold Cup for Canada. “But mind you, right after that, again, we didn’t do that well in World Cup qualifying.”

For de Vos, a long-time advocate of reform to Canada’s player-development system, the lack of ongoing success was no accident. While the Gold Cup win was an exciting moment for the players and hardcore fans, it may have actually served to gloss over the program’s deep-rooted problems.

“Without a long-term plan in place, we are literally making it up as we go along. We can’t continue to do that,” he says. “Here we are now, 15 years on from our greatest achievement on the men’s side in winning a CONCACAF championship, and I don’t know that we’re any further along now than we were then.”

The Canadian soccer landscape has, however, changed since 2000. At the grassroots level, the Canadian Soccer Association is implementing a long-term player development plan in the hopes of finally translating massive youth enrollment numbers into national-team success.

At the professional level, the country now has three MLS teams (each operating their own academies and affiliate teams in USL) and two teams in NASL.

“I think it’s definitely heading in the right direction,” says Nash, who is assistant head coach of the NASL’s Ottawa Fury. “The MLS teams have been running academies, and there is some good talent coming through.”

There are also players who have found their way to the top through other means, such as rising star Cyle Larin, who played for a local private academy before playing NCAA ball with the University of Connecticut.

Watson, who is now an assistant coach at Orlando City, has had the chance to see Larin grow during his rookie season with the Lions. While Watson lauds Larin as a player with “incredible tools,” he wonders how things could have been different if player-development reform had come along earlier in Canada.

- Group B preview: Costa Rica are the favorites in Group B free-for-all

“What would [Larin] be like if he was in a really good program from 10 years old or 12 years old?” says Watson. “He’s one that just has a ton of natural ability, and he’s getting his education a bit later than you’d hope, but he’s doing really well.”

But with youngsters such as Larin – and a generation of Homegrown Players like Jonathan Osorio, Russell Teibert and Maxim Tissot – there is some positivity about Canada’s chances at this year’s Gold Cup. Head coach Benito Floro has stated that the goal for his team is to win the tournament.

The Canadians are, of course, massive underdogs, same as they were 15 years ago. But with everything that has changed since then, would a 2015 Gold Cup win provide the sort of resonant turning point that the 2000 Gold Cup could have represented?

“It would be a bigger deal than it was previously, and it would be a step in the right direction,” says Watson. “Though if you’re looking at team results, I think it still all revolves around the World Cup.”

Indeed, veterans of the 2000 squad – which was inducted into the Canadian Soccer Hall of Fame last year – seem to agree that while a deep Gold Cup run would be a welcome shot in the arm for the program, it too would be forgotten unless it’s followed up with ongoing, sustainable results. Those are only likely to come once the recent changes in the Canadian landscape start bearing fruit.

“I do not fault the men’s or women’s national team head coach for doing everything they can to win now, because that’s their job,” says de Vos. “But we have to marry that with a long-term plan for the next generation.

“We owe it to our kids to do something better for them, because if we don’t, we’re going to keep getting the same result, which is not good enough.”