Apparently we are still living in the Lovecraftian nightmare edition of the US men's national team reality, because there was probably one thing we all wanted most out of this now complete international date: No major injuries to key players.

And so naturally first Weston McKennie (long term) and then Christian Pulisic (hopefully not long-term, but who the hell knows) – arguably the two best players on the team, and two-thirds of the holy trinity of youngsters destined to drag the US out of the most recent World Cup cycle's abyss and into the light of a new, more successful day – both limped/hopped/were stretchered off the field. Cool.

McKennie has what Schalke termed a "ruptured" ankle ligament, and I've seen various reports suggesting his recovery time could be as short as eight weeks, and others saying as long as six months. Pulisic's quad injury is as yet not officially diagnosed, but he certainly seemed to be in less pain than McKennie, and hopefully will spend less time on the mend.

Regardless, this has become the norm for the US: Lovecraft's Great Old Ones climbed out from the bottom of the sea and dragged two of this cycle's great hopes back down to the depths with them.

Hopefully this is a very temporary state of affairs. It is dispiriting.

But what is not dispiriting, following last week's 1-0 win over Ecuador and Tuesday's 1-1 draw against Chile, is that the US clearly had a plan, clearly stayed with the fundamental parts of it, and clearly bought in – up-and-down the roster – on attempting to execute it. They were, to use head coach Gregg Berhalter's word, brave.

"I learned that the guys are resilient; also I learned that we were pushed to the limit today and the guys hung in there, when you see the effort that the guys put in there,” said Berhalter in the postgame presser.

"Overall, I think we made it extremely difficult for them and I thought we showed the bravery to try to play through some of [Chile's] pressure.”

There is a lot of wailing and gnashing of teeth amongst the US fanbase today, mostly centered around the US's inability to control the game and/or carry much of play against Chile's first-choice squad. Damn near all of said wailing and gnashing of teeth misses the fact that A) the US team that was out there had played exactly zero games together, while Chile's squad was full of veterans with two Copa America titles and 100+ caps, and B) McKennie and Pulisic, Tyler Adams and Zack Steffen, John Brooks and Aaron Long (all first-choice players) are all, at this point, essential to the US's ability to build from the back.

Let's sum it up: The US second string, with zero reps together, struggled to play through the Chilean press that's led to the two most recent Copa America titles. Dog bites man.

It's fair to say the system Berhalter put in place didn't exactly shine. Nor, however, did it crumble, and the good thing about actually having a system is that when good, veteran teams expose one or more elements of said system, you have a framework for how and where and why to adjust.

To that point:

Much has been made of the way the US becomes a 3-2-2-3 when on the ball in attack under Berhalter, but against Chile we saw almost none of that. Partially it's because the US were without the six guys listed above, but partially it's because Chile were able to put so much pressure on the US's defensive structure by repeatedly finding their own midfielders (Arturo Vidal in particular) in between the lines of the US's midfield and defense.

That defensive structure is as much a part of the burgeoning US identity as the attacking structure. The US, under Berhalter, play a mid-block 4-2-2-2 when defending against a team in possession, and in general my worry is that transitioning from the front-foot, ball-dominant 3-2-2-3 to the rock-solid 4-2-2-2 will be the moment where the US gets exposed.

They did not get exposed in those moments – Chile had basically nothing in transition. But as the clip above illustrates, and as the build-up to Chile's goal illustrated, the US were exposed pretty constantly when playing out of their basic defensive structure.

It was concerning, but it also prompted a useful and damn near game-changing adjustment as Berhalter sacrificed a winger for a wingback, shifting from the 4-2-2-2 defensive shape to a 3-4-3 in the 57th minute.

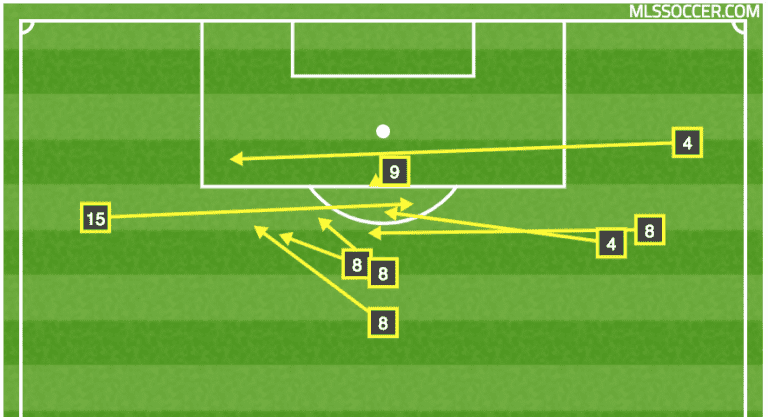

Here are Chile's key passes (passes that lead to a shot) in the first 57 minutes of the game:

That is indicative of a team experiencing something close to a defensive nightmare. The fact that the US allowed so few looks despite Chile setting up shop in Zone 14 speaks to how well the defensive midfield and center backs were able to scramble.

But Berhalter's teams aren't about scrambling: They're about denying your ability to force them into scrambling situations in the first place.

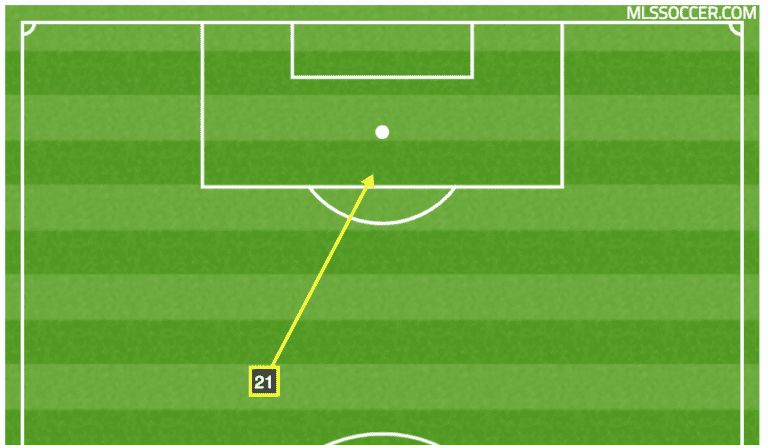

Here's Chile's key passes for the final 33 minutes of the game:

Shifting the shape of the US defensive alignment shifted the shape of the game. The US went from a faux single pivot with two center backs in behind to a double pivot (first Cristian Roldan, and then Wil Trapp dropped deep to help Michael Bradley, who was getting overrun) with three center backs, as well as two wingbacks providing additional support. After getting battered from minutes 15-57, the US shut the game down for the final 33 minutes and actually had the better of play/more dangerous moments going forward down the stretch.

My colleague Bobby Warshaw has a slightly different take on the above:

What we saw wasn't someone who made adjustments, but rather someone who has built a fully cohesive plan that covers every phase of play. Everything about Tuesday's plan was the same as last Thursday's plan, except the game was played in a different phase. The Ecuador game emphasized the attacking (possession) phase and defensive transitions; the Chile game demanded more from the US in the defensive phase and attacking transitions. If the US could have gotten more of the ball against Chile in the attacking half, they would have played it the same way they did against Ecuador. Some coaches prepare more for or build a style specialized for certain phases. Berhalter showed on Tuesday that his plan accounts for all of them.

The flexibility isn't about the plan – the plan doesn't change because it doesn't need to – it's about the personnel within the plan, and picking players for each spot that fit how the plan will be used on that day.

Whether you consider it an actual adjustment or just the flexibility that's baked into Berhalter's gameplan and personnel choices, there are more things from Tuesday's performance to be heartened by than discouraged by. This is especially true given how obvious it is that Berhalter is a coach who knows how to diagnose what is actually happening out there:

These two friendlies are indicative of a team that's absolutely ready to smother an opponent that's bunkered in, as well as one that's ready to shift on the fly if they need to against an opponent that's grabbed the upper hand. The system and the approach to implementing it allow the lessons of one half to be applied to the next, and the lessons of one camp to be applied to the next.

Slow, steady, forward. With a plan.

The Big Winners

Aaron Long and John Brooks: If they stay healthy it's hard to imagine they're not the first-choice pairing for this summer's Gold Cup. Matt Miazga might have something to say about Long's spot, but he'll have to play really well for a Reading side in "hanging on for dear life" mode.

Wil Trapp: His passing was a weapon (as expected) against Ecuador, and defensively he was excellent. Then he came on against Chile and was a huge part of shutting them down and putting a steady hand on the wheel.

The most important thing, though? He never looked out of his depth on a physical/athletic level. That's always been the big worry with Trapp, and it's now three straight USMNT appearances in which it hasn't been a thing.

Gyasi Zardes: A goal against Ecuador and an assist against Chile. Some battling, surprisingly classy hold-up play against both teams.

He's not the No. 1 striker in the pool, and I will be something in the neighborhood of apprehensive if he's the starter for this summer's Gold Cup. But everyone should've come away from these two games with more confidence in Zardes's ability to be an asset in the right situation.

Probably Didn't Do Enough

The Wingers:Paul Arriola battled and got into good spots. Corey Baird battled and got into good spots. Jordan Morris was a little bit lost, but had some god moments. Jonathan Lewis is a shot of caffeine when he comes on late, and his ability to beat defenders off the dribble is an asset.

None of them made match-winning plays when the moment arose, and that's a problem because in this attacking scheme, the wingers are often the ones asked to win the match.

I remain convinced Pulisic should play wide on one side or the other.

Cristian Roldan: Struggled to make any sort of mark on the game on either side of the ball against both teams.

Tim Ream: One gigantic mistake per game is understandable in a 21-year-old who's new to the international level, but Ream's a 31-year-old EPL vet. It's amazing that this still happens.

Biggest Questions Between Now and June

Where do we use Pulisic?

I've written about this one a lot already, and his 35 minutes against Chile were a good advertisement for his functionality as a through-the-lines No. 10 playing off a center forward with hold-up instincts and passing ability. I mean, if Pulisic can do that playing off of Zardes, what happens when he's playing off of Jozy Altidore or a hopefully-more-fully-developed Josh Sargent?

That's the argument for. The argument against is that stuff above about the wingers? I'm not writing that stuff if Sebastian Lletget is the No. 10 and Pulisic is out wide on one side or another.

Will Sargent and Tim Weah be ready?

I regret to inform you that neither has played much for their clubs over the past month after a promising start to 2019. They both played quite a bit for the US U-23s this past weekend and while Sargent continued to look slow and unsure of himself, Weah was fairly dynamic and could be a huge part of the answer at right wing for Berhalter.

Does slotting Adams next to the No. 6 from the start make more sense?

That one probably depends upon the opponent, but I wouldn't be at all surprised if there was a 3-2-4-1 with Adams on the "2" line waiting for Mexico. Against everyone else in Concacaf, what we saw against Panama, Costa Rica and Ecuador is probably on the menu.

Are there any other young players to keep an eye on who might be of help?

Sargent and Weah are obviously on everyone's radar.

Antonee Robinson had a good weekend with the US U-23s, and we've all seen him with the full national team before, and he obviously plays a position of need. It's worth questioning whether he can play left back the way Berhalter wants it played in this system, but as long as he stays healthy he'll be going 90 every week for Wigan for the rest of the year. Watch that.

Is it too soon to suggest Paxton Pomykal could slot into McKennie's spot should McKennie miss the Gold Cup? Or could we see Djordje Mihailovic return to the full US squad? I'd say "probably" and "maybe," respectively. But man has Pomykal been good, and if including him means pushing Pulisic to the more dangerous winger role...

Should we be happy?

I mean, I'm not ecstatic or anything, but I'm enjoying watching a process-oriented men's national team for the first time in a long time, and that's a major step forward for the program. And I'll point this out as well:

- USA: .67

- Chile: .56

That's the expected goals total from Tuesday night as per Opta. So even against a Chile team that was pretty desperate, and playing pretty close to their best XI against a team of US second-stringers that's still sort of hacking through the brambles with regard to the system and personnel... xG totals aren't everything, but they ain't nothing.

Which brings me back to the very beginning here. If the No. 1 thing we should all have wanted to see from this camp was "no injuries!," running a close second should've been "please let us be a team that's hard to beat."

We haven't really been that for a long, long time. Through four games of this new era, we seem to be trending back in that direction as the US structure, a good adjustment and some pretty battling performances on the backline didn't let Chile's hour worth of positional dominance turn into actual dominance. This team is now hard to beat again.

It's an important building block, and an important return to the identity of the best US teams of years (and decades) past. And dispiriting injuries or no, that points toward a much brighter future.