EDITOR'S NOTE: This year, MLS and its community outreach initiative, MLS WORKS, launched a new platform, called "Soccer for All." Soccer for All signifies that everyone is welcome to MLS, regardless of race, color, religion, national origin, gender, disability, sexual orientation or socioeconomic status. MLS embraces the diversity of our league and is committed to ending discrimination by driving positive social change and fostering more inclusive communities.

Last week, I got right to the point. I asked Denis Hamlett, longtime MLS player and coach and now sporting director for the New York Red Bulls, what the future looked like for the black athlete in MLS.

He got right to the point, too.

"I would hope that young black players from around the world can see MLS as a platform for them to continue their development and have an opportunity to fulfill their dreams," Hamlett said. "In terms of big picture, that would be the ultimate goal. Then to see our national team represented with those players. When you look around, this country is built on diversity, and when you look at it from all walks of life, that's what makes America great. That, from both perspectives, is to have a league where people can see that and a national team where people can see the same."

Denis Hamlett is sporting director for the New York Red Bulls | newyorkredbulls.com

Hamlett said that although MLS is young, it has made tremendous strides toward being more inclusive. Not for the sake of pandering to minorities – diversity helps the league to reflect the world in which it exists in.

Still, Hamlett would like to see more minorities in upper management and in the coaching ranks. Currently, he is one of two black technical/sporting directors in MLS, along with the Philadelphia Union's Earnie Stewart, who was the first African-American hired to that position since the league's inception in 1996. Patrick Vieira is the only black coach currently in the league.

Change is a slow process, but the nature of the game today is much different from years past, when the numbers of black people in coaching and upper management were almost non-existent. Because of this, Hamlett appreciates the gravity of his position and the importance of representation. He is an example for others who look like him, having achieved a goal they could strive toward in order to both showcase their talents and intelligence as well as help break the homogeneity of the game's power structures.

Soccer in the United States has long been a middle-class sport, which inherently has led to discrimination, so the few that beat the odds and get into the spotlight bear a burden as leaders and inspirations for future generations. The kids need heroes. They need to know that people who look like they do can reach the top: People like Cobi Jones, Eddie Johnson, Jozy Altidore, Tyler Adams and Kellyn Acosta.

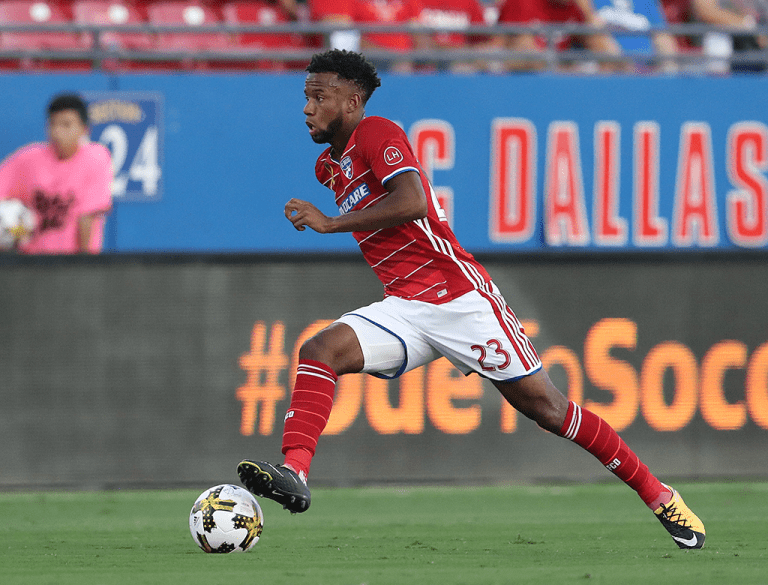

Kellyn Acosta joined FC Dallas Academy in 2009. | Matthew Emmons/USA TODAY Sports Images

Acosta is a unique case, not least because of his racial makeup. The term "black" encompasses and compresses so many different types of people that it's easy to lose track of the multitudes that exist within it. This is especially evident in the soccer community. Black can be used to refer to Altidore, who is African-American but born to Haitian immigrants. It can refer to Warren Creavalle, who was born in New York but has Guyanese ancestry and plays for Guyana. And it can refer to Acosta, who has a black mother and a white father, even as his father was born in Japan and his grandmother is full Japanese.

Yet Acosta's story is an American one that resonates with all the cliches of hard work, perseverance and luck. A story that exemplifies what it takes to make it to the next level, even for kids who might fear they will be overlooked.

Acosta grew up playing soccer at the elementary school in front of his house with no other goal than improvement. He was signed to the FC Dallas Academy, where he found coaches who didn't care about his heritage or his background. They simply wanted him to develop. They had his best interests at heart, he says, and they offered something many others don't: a clear pathway to the first team.

By the time Acosta was 17, he was with the first team, and just a few days after he turned 18 (in 2013), he debuted. Since then, he has become one of the top midfielders in the league, earned his first cap for the US National Team, and won several trophies for both club and country.

Acosta, now 22, champions Dallas' academy system as the example that other teams should follow in scouting players. He believes that FCD's coaches look for players who might fall through the cracks elsewhere. Players like himself, who could have easily been another wasted and forgotten talent.

"I think what the academy system is doing right now, I think it's going in the right direction," Acosta told me recently. "I think [the academy coaches] really do a good job of finding some of these kids who are more low-key than others. It's easier to go to these big [youth] clubs and invite them from there. The harder job is to find players that play at these small clubs and bring them about."

Warren Creavalle, who now plays for the Union, echoed others' optimism for the future for black soccer players and the need for more resources to make the game more accessible and diverse. But he also had a personal mission that goes beyond what can be done on the field and in the staff offices. It comes to life in an eponymous apparel and photography brand, CREAVALLE, that aims to reflect and inspire a player's cultural life.

If Hamlett is the representation in upper management and Acosta is the shining star on the field, Creavalle wants to be the paradigm for the antithetical athlete. He wants to show a player who might not have been introduced or had access to art growing up that there can be a balance between sport and the creative life.

"I want to introduce kids to different elements at a younger age," he says. "Growing up, I thought all I wanted to do was to play soccer. I think if I was introduced to those different things, I would have had more of a balance. I think we need to show the kids more options to succeed than what society is showing them. That's my goal."

Which leaves us with an idea of a future that is bright for the black player. It is bright in different ways. A change is coming to the game. It has to come simply to reflect the world around it.

There are black pioneers in upper management trying to change the status quo and at the same time showing the younger generation that their sporting life doesn't have to end after their playing career. There are great black players who act as proof that the upper echelons of the game are indeed reachable. And there are players who are working on empowering young black kids beyond what they can do on the field.

Individuals can't change a system on their own; the system has to be welcoming to it. And that change always begins with a few individuals ready for it to exist. That's the start. Now where does it go from here?

ZITO MADU was born in Nigeria and grew up in Detroit. A lifelong soccer player and fan, he writes at the intersection of sports and culture for SB nation and has been featured for GQ.