Part 2 in a 2-part series (click here for part one)

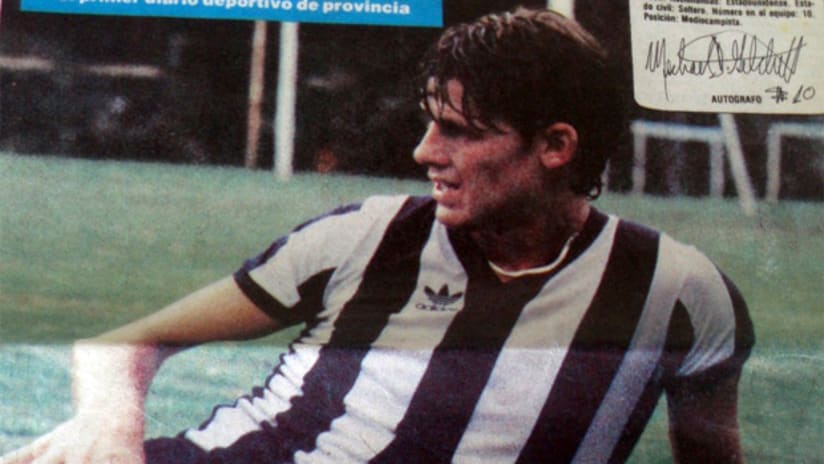

He was the first American ever to play in the Mexican Primera División, with Monterrey back in 1988. Michael Getchell had broken a barrier he barely realized existed.

“I guess I knew [I was the first American], but so what?” he recalled. “Nobody ever called me and said, ‘Wow that’s interesting.’ I just went on with my life.”

That wasn’t so easy. On the field, he had to adjust his game dramatically. Playing on a surgically rebuilt knee, he no longer had that extra step to play his preferred attacking midfielder role in the fast-paced Mexican game. So he drifted back to the holding position.

Getchell’s innate talents were still apparent, though, and he slowly made his way into manager José Ledesma’s regular rotation. After dropping out of the game-day roster, he worked his way into the starting lineup, and became somewhat of a sensation at Monterrey. The press loved to follow the trials of their gringo, and the fans appreciated his competitive nature on the field.

Away from the cameras, it was a rough go. There were few welcoming handshakes from the majority of his teammates. Many of the club’s players, who were local products, were outright adversarial toward the norteño in their midst. This was a guy, they believed, who wanted to take their spots on the first team.

“This was the situation,” he explained. “I looked like an American, with blondish hair and blue eyes. The fact that I looked that way, and that I claimed I played soccer, created suspicion with a lot of people.”

Getchell made few friends at Monterrey, other than a few South Americans on the team, and wasn’t included in the players’ social outings. He picked up Spanish as best he could, which was slightly easier thanks to being fluent in Portuguese. Eventually Getchell began teaching college courses in political science in English just for regular interaction with people. But it was still a lonely existence.

“My dream as a kid was always to become a pro,” he said. “But I never imagined it ever would have been this hard. I felt very alone.”

His love of the game was what got him through. Getchell dished out a couple of assists that year and relished the experience of playing in Mexico City, Guadalajara, Laguna and, especially the Monterrey clásico against crosstown rival Tigres.

But by midseason, it began to come apart. Getchell had become a regular starter, but the last-place Rayados were struggling. By February ’89, Ledesma was sacked and replaced by Chilean World Cup veteran Fernando Riera, who didn’t share his predecessor’s love for the American on the roster.

Getchell felt the pressure of losing and of having to prove himself over again in unfriendly territory. When his frustrations boiled over, he booked a permanent place in Riera’s doghouse. Getchell went in hard on an attacker in a match at Toluca, and his harsh challenge incited an on-field brawl. He was red-carded and suspended for six games, and would only make sporadic appearances the rest of that season as Monterrey finished in the cellar in their group.

He would never play for Monterrey again. Getchell stuck around for the following preseason, but Riera maxed out the club’s international-player quota with South Americans. There was no more room. And the writing was on the wall.

“I made a half-dozen calls to other clubs,” he said, “but had no luck. I felt blackballed, really.”

Getchell went home with great experiences and memories under his belt, but he admits it was overshadowed by a feeling of disappointment of how it ended, and never getting the right exposure for another U.S. call-up.

He finished out his playing days back in the pre-MLS American leagues, a season each with the Los Angeles Heat and the Colorado Foxes, before hanging up his boots for good in 1991.

“He was ahead of the game in terms of where the game was [in this country] at the time,” UCLA teammate Caligiuri told MLSsoccer.com. “Things were different then. There weren’t a lot of opportunities regardless of how good a player you were. His timing was really unfortunate.”

Today, the mention of Getchell’s name draws a shrug from most of the American public. Google his name and you’ll find few traces of him. Monterrey has no records of him. Venerable Mexican soccer website mediotiempo.com doesn’t even spell his name correctly. Not even Getchell’s own family believes him sometimes.

“I tried to contact the club to see if they had any photos to show to my kids and nephews because nobody believes me,” he laughed.

But his legacy is intact, if even quietly. Getchell opened doors, both literally and figuratively. His recommendation to the president of Cobras de Ciudad Juárez helped land Cle Kooiman his first gig in Mexico in 1990. In later years, Mike Sorber, Dominic Kinnear, Tab Ramos and Marcelo Balboa followed.

Getchell, however, faded out of the limelight. He eventually took a marketing job with equipment-manufacturer Umbro and moved back and forth between California and Brazil. Today, he’s a consultant living in São Paulo.

He still plays in an adult league – and well, he adds – but he doesn’t follow the American game much, and has never heard of gringo sensations Herculez Gomez or José Francisco Torres. But they should know of him, says Caligiuri.

“A few of us [Americans] had to make opportunities out of nothing,” said Caligiuri of his old college teammate. “Those guys are pioneers. Getchell, especially so. That was his determination. If he didn’t break down a barrier, he would have climbed over it. We should all be thankful.”

Jonah Freedman is the managing editor of MLSsoccer.com. “The Throw-In” appears every Thursday.