What’s a “holding” midfielder? I’m not really sure. To be honest, I don’t think anyone is.

The term is applied pretty liberally across the board. Is it Andrea Pirlo? Is it Michael Bradley? Is it Osvaldo Alonso?

It can’t — it really can’t — be all three. They’re vastly different players who excel in different areas of the field, yet all three are commonly referred to as “holding” midfielders.

Soccer, you see, needs new words. And it’s all Carlo Ancelotti’s fault.

The problem goes back to Pirlo, who was the canary in the coal mine. The AC Milan and Azzurri star was hard to peg early in his career, bouncing around Italy without a permanent home at a club or on the pitch. Finally, he settled into the Milan lineup at the ripe old age of 22.

[inlinenode:327733]Not one of his managers, at that point, could figure out quite what to do with him. They didn’t know what he was, how to play him on the field or who to put around him. They just knew he was talented.

Then Ancelotti, now fighting for his coaching life at Chelsea but forever a legend with Milan, had a “eureka” moment: He’d move Pirlo to the spot just in front of the central defense — a spot then occupied almost exclusively by the “defensive midfielder” — and ask him to make plays from there.

Ten years later and most of the footballing world has caught up to the shift in tactics. Both MLS Cup finalists last year used a tactical approach similar to that of Ancelotti’s Milan, as have with countless other teams from Manchester United to die Mannschaft.

But while the game has evolved, terminology we use to describe that shift has barely changed at all.

Pirlo is described, rather clunkily, as a “deep-lying playmaker” or, frustratingly, as a holding midfielder (which means nothing). Ten years ago positions were more rigid and defined: Didier Deschamps was the defensive midfielder, Zinedine Zidane was the attacking midfielder. Deschamps hardly ever had work to do in the attack while Zidane was freed of defensive responsibilities.

Now, we call a player like of Gennaro Gattuso a "defensive midfielder," even though he almost never plays that position. Instead he prowls deep into the midfield of his opponent, trying to force turnovers that his more skillful teammates can turn into chances.

The fact that those skillful teammates are largely deployed on the wing nowadays is a testament to how effective the Deschampses and, if you want to keep it MLS, Chris Armases of yesteryear were at winning the “d-mid vs. a-mid” battles. The a-mids had to get out of the middle of the pitch in order to find space to operate.

[inlinenode:327363]The Gattuso role now requires an extraordinarily high level of stamina and range, because you have to be able to cover from box-to-box and touchline-to-touchline for 90 minutes. This is why the term “holding” is so badly misused. It’s also why Bradley is so effective in the spot: He has superhuman stamina, as his heat maps from last summer’s World Cup can attest.

Bradley is part of a new wave of these “disruptors” who’ve even added a facet beyond what Gattuso brought: finishing.

Earlier this week, Sounders manager Sigi Schmid told reporters that Brad Evans, when healthy, plays the Gattuso/Bradley role in Seattle:

"One of the other MLS coaches who's a friend of mine, one of the first things he said when we saw each other was, 'Do people realize how much you miss Evans? He has the ability to make those late runs in the box, which are so hard to defend,'" Schmid said. "I said, 'I don't know if everybody realizes that.'"

In MLS, the change in tactics is embodied in the career of Pablo Mastroeni. The Colorado Rapids man was long a US national team stalwart as a d-mid, the Deschamps of the Red, White and Blue, a position he played at the club level as well.

Until 2010.

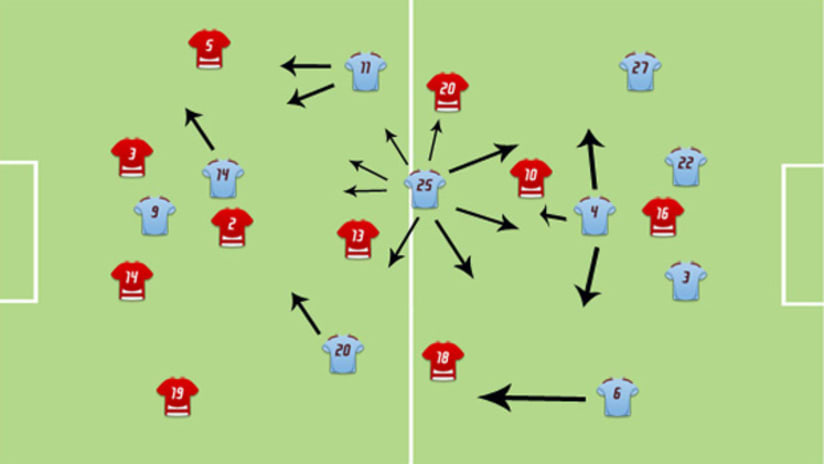

Take a look at the graphic at the top of the page. This past year, Colorado Rapids coach Gary Smith had Jeff Larentowicz (No. 4) play the Pirlo role, a “deep-lying distributor,” while Mastroeni (No. 25) was pushed higher up the pitch. Instead of shielding the back line, as he’d done most of his professional career, Mastroeni spent much his time 50 yards or more from his defenders.

His ability to cover ground frees up the fullbacks – most notably Anthony Wallace (No. 6) to push fully into attack. It also allows room for wide midfielders Jamie Smith (No. 20) and Brian Mullan (No. 11) to press inside in possession, giving the Rapids an unpredictable element in the final third.

[inlinenode:323654]Mastroeni is still called a d-mid by most, but that’s clearly not what he does anymore. His high pressure creates turnovers, but not the classic “turnover from a tackle.” Instead, the focus is in forcing bad passes that lead to interceptions, the most effective way to start the break.

Anyone who remembers the Rapids playoff performance is nodding right now. From 2002, when he joined the Rapids, to the end of 2009, Mastroeni had two goals in all competitions for his club. In 2010 alone, he had three. He also had three assists and could have had another early in the Cup when he put Mullan through on goal off – yes – a turnover.

OK, so Mastroeni’s not exactly a scoring machine. But that three goal tally wasn’t insignificant, especially since those late runs into the box opened up space for the rest of the attack even when he wasn’t scoring himself, and because those intercepted passes were the lifeblood of Colorado's offense.

So ... is he a d-mid? Is he a holding mid? Is he simply a central midfielder? And what are Pirlo, Gattuso, Bradley et al?

Right now, we just don’t have the words to say.

Matthew Doyle can be reached for comment at matdoyle76@gmail.com and followed at twitter.com/mlsanalyst.