In the first leg of the 2018 Eastern Conference Championship, New York Red Bulls head coach Chris Armas told his players to start their defensive pressure near midfield. It caught almost everyone off guard. The Red Bulls...not pressing high? You know what happened in the game. Atlanta Unitedwon 3-0.

The decision didn’t just potentially end Red Bulls’ season. As the Red Bulls start preseason this week ahead of the 2019 Concacaf Champions League, it could set the course for their future as well.

Starting defensive pressure near midfield is not uncommon for most teams. But it is for Red Bulls. They are a high pressing team that rarely drops and waits. They turned to their Plan B for the game.

Most observers acknowledge that Armas’ decision was logically sound. In the tactical chess match, not pressing Atlanta – who were predetermined to play direct to bypass the press anyway – made plenty of sense. I’ve argued that it was the correct decision outright, but I cede that there’s a valid point to be made to the contrary.

The problem arose from the players’ lack of familiarity with the tactic, and thus the inability to execute. It wasn’t the tactic that was the problem, but rather the change from their usual playing style. The unfamiliar style made everyone play with less conviction.

It wasn’t a singular decision for Armas. It’s now one the biggest questions confronting him -- and many other managers around MLS – heading into 2019: What’s the role of tactical flexibility? Is the concept of having a Plan B dead?

Tactical versatility is wonderful in theory. Every tactic has a kryptonite, so you should be able to adjust. If you always throw a right hook, opponents will learn to get their left hand up to block. The good opponents will also counter with a jab.

But the Red Bulls have taught us an important lesson over the last half decade. Everyone knows the Red Bulls want to throw a right hook. But if your left arm isn’t strong enough to block the hook, you’re still getting punched in the face. And that’s why the Red Bulls have been so dominant in recent years over the regular season: They throw a harder right hook than anyone can block. It’s not about the idea; it’s about the execution.

The best description of tactics I’ve heard is the line: We aren’t trying to pick the best way to play, we are trying to pick a good enough way and do it together. The strength in tactics isn’t out-smarting the opponent; it’s out-executing. If you do what you do better than the other team does what they do, even if their way is theoretically superior, you will win.

Teams are so good at doing what they do now, that if you can’t execute your plan as well you will almost certainly lose.

The Red Bulls are the best example, but the idea of a consistent, overpowering style has taken hold across MLS. In 2018, nine of the 12 (by my count) playoff teams used the same specific style in just about every game of consequence. Conversely, the teams that swapped between formations and tactics generally finished bottom of the table. (Begging the next question: Did they switch because they were bad, or were they bad because they switched?) There’s a clear pattern.

So time for the nuance.

There are two separate questions at hand. First, what’s the role of tactical flexibility in low-to-mid level teams?

I think the answer should be: Zero.

The bar of sufficiency on tactical execution has been raised. It’s clear that being excellent at one thing is more useful than being mediocre at multiple. The only thing worse than not having flexibility is not having any mastery.

Second, what’s the role of tactical flexibility in good teams? This one is much more complicated.

Toronto shifted between multiple formations en route to three trophies in 2017; Sporting KC pressed, rather than passed, their way to a win over RSL in the 2018 playoffs; Atlanta threw NYCFC and RBNY a surprise this postseason. Armas got crushed for his decision to adjust for the playoffs, but "Tata" Martino was revered.

Why did it work out for Atlanta but not New York? Is there something about the Red Bulls' plan – or any other team's – that’s inherently difficult to adjust?

What’s specifically tough for singularly focused teams like the Red Bulls is the type of player necessary for their primary style. To execute a tactic to the required level, players need to fit that specific profile. The specificity of the original style makes it tougher to develop a secondary style. We saw in the Atlanta game that Daniel Royer and Alex Muyl – players used for their ability to win duels – struggled to create any problems on the counter in open field.

Tactical flexibility isn’t dead. It’s just harder than ever. To be a good team, you need to be able to do one thing well. To be a great team, you need to be able do multiple things as well as the good teams do their one.

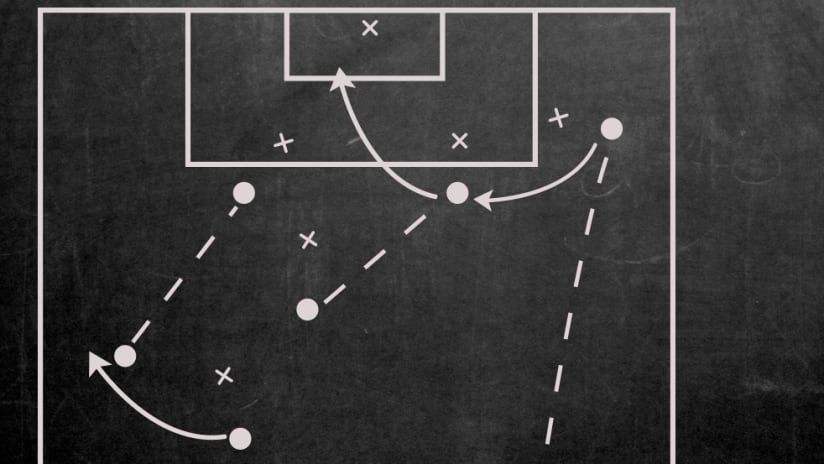

The key seems to be that the great should build on the good. It should be variability within a general framework. It’s more of a Plan A, with A.2, A.3, A.4. They are small adjustments: players with similar styles but different attributes, positioning of the outside backs when building out of the back, rotation of the center midfielders to find the ball, movement from the wingers in the final third.

And it helps if the manager is building on previous years. A manager usually hones in on a single concept the first year, then adds wrinkles later. It’s no coincidence that Sporting Kansas City might be the most sophisticated tactical team in the league after more than eight seasons under Peter Vermes. In those situations, it’s a question of the depth of the wrinkles. How much can we adjust without losing our ability to execute?

Having a Plan B is nice. But every minute spent working on variability is a minute not spent on perfecting Plan A. And if you can’t execute a Plan A, you’re almost surely destined to lose.