The United States Women's national team has been the focus of a lot of criticism around their occasional reliance on a "long ball" style of play.

Abby Wambach, their talismanic target forward with an extraterrestrial ability to wrangle herself on the end of long balls and deep crosses has, naturally, been central to this debate. It makes sense – her last-minute header in the 2011 World Cup quarterfinal against Brazil via a wicked Megan Rapinoe cross is one of the more famous goals in USWNT history, with Rapinoe claiming later that there was "only one person in women’s soccer who could’ve finished it." She's right. Wambach, even four years later, remains a game-breaking force in the women's game.

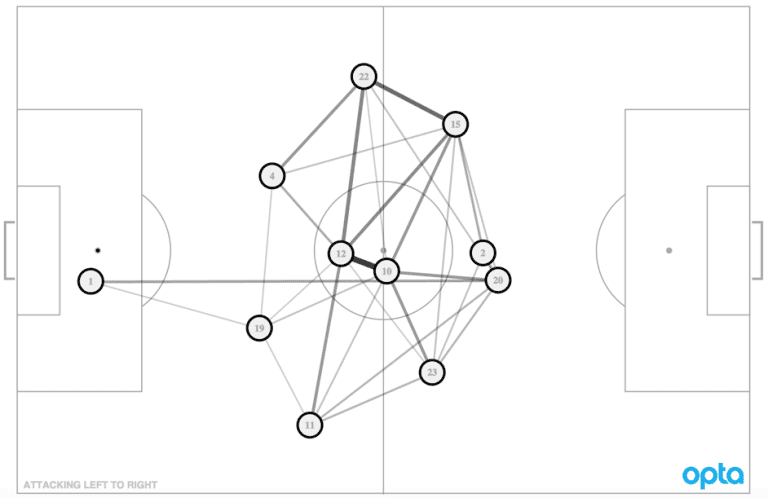

While the United States managed to carry the majority of possession in their 3-1 win against Australia in their Women's World Cup opener – a distinction that "long ball" oriented teams rarely achieve – their passing network diagram retains shadows of an Abby-centric style of play.

Wambach exchanged nine passes with her goalkeeper, Hope Solo, over the course of the match. That connection is stronger than any of Wambach's other individual connections save the 10 passes exchanged with attacking central midfielder Carli Lloyd (No. 10). In addition, Wambach's connections with outside backs Meghan Klingenburg (No. 22) and Ali Kreiger (No. 11) are just as strong as her connections with outside midfielders Christen Press (No. 23) and Rapinoe (No. 15). Receiving the ball just as often from your outside backs as your wingers is further evidence of her primary responsibility as a target player.

Many of the arguments lamenting "long ball" style call it deeply regressive and behind-the-times. There is no doubt that this style is becoming antiquated in both the men's and women's games, but there's more to the “long ball” game than most detractors claim. While possession doesn't win games, possession in dangerous areas sometimes does. And Wambach, so adept at being an outlet for those up-field passes, is a wonderful outlet for quickly getting the ball into very dangerous areas.

- Women's World Cup: USA opener draws record TV audience

Game theory insists that some form of "long ball" style will always be viable, regardless of if it's in vogue. If nothing else, modern tactics are cyclical. If a team focuses on restricting a specific style of play, they always become susceptible to being exploited by another approach. "Long ball" style is just the latest target in this infinite game of tactical whack-a-mole. And while "long ball" has largely morphed into "direct play" on the global stage, many of the same principals remain.

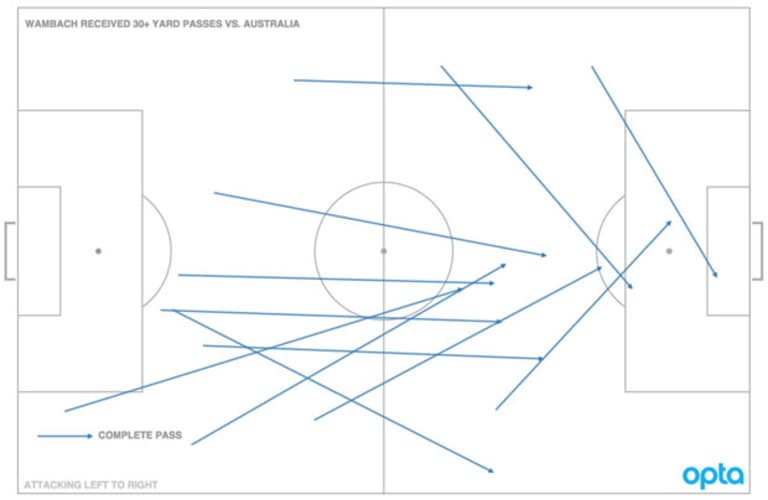

Wambach received 12 passes from "long" distances during the game against Australia, which we will define as passes longer than 30 yards in distance. Given that the United States enjoyed 135 possessions during the game, one out of every 11 possessions included a completed long ball to Wambach. There were plenty more possessions that included a failed attempt to the target woman.

For comparison, MLS's league leader in long passes received is Alan Gordon, and he averages 9.9 long passes received per 90 minutes.

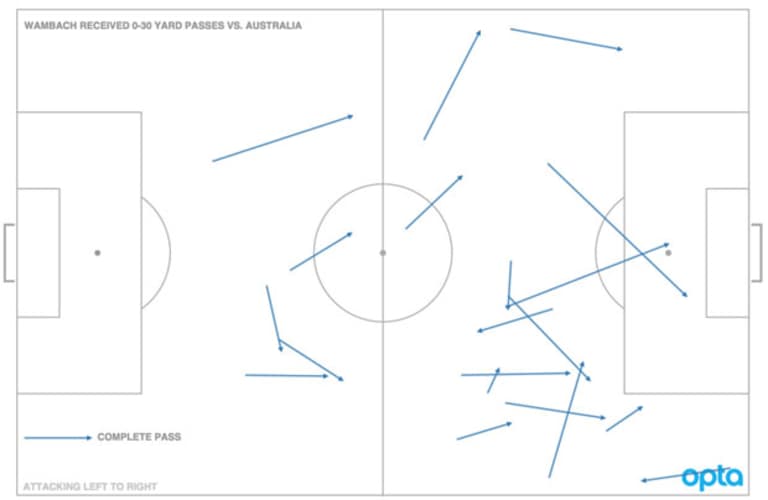

But Wambach's long passes received aren't what worry this analyst, it's the shorter passes she demands into her feet that I think are the primary concern. Wambach makes it difficult to play to her strengths when she drops into the midfield to receive the ball. Without a target up top, the US system is pulled out of balance, allowing opponents to collapse upon the midfield.

Center forwards receiving the ball in deeper-lying positions is something out of the book of the "false nine", a fairly modern tactical innovation. This is an effective strategy when the striker possesses superior playmaking abilities to punish central defenders for chasing them into the midfield. However, Wambach is never going to be a provider in the same stratosphere as US central midfielders Lloyd and Lauren Holiday. When Wambach drops into the midfield to receive the ball (no matter if she's successful or not), it causes a cascading loss of structural integrity in the US system of play. Suddenly without a viable vertical outlet, it makes pressing the US midfield a lot less dangerous.

In other words, the tactics aren't stuck in the past as much as they're being misused. If Abby is going to remain in the starting lineup for the US, they desperately need her to stay out of the engine room and stretch the field for her teammates.

Perhaps the conundrum the US team is facing is now clearer. They must rely on a one-dimensional player to play exclusively in that single dimension to allow their more-dynamic assets to shine. This single point may cause heart palpitations, but it is the price that Jill Ellis needs to pay to keep her game-breaking force on the field. Retaining Wambach in the starting lineup would be a high-risk, high-reward decision, but that's perhaps the mentality it takes to win a World Cup.