PACHUCA, Mexico – The soccer gods intervened again.

Researching the city of Pachuca, Mexico, prior to getting there, I’d developed a healthy fascination with visiting its University of Soccer and Sports Sciences. But no one had responded to my polite emails.

Johnathan De Oliveira, a Montrealer working as a fitness coach for Pachuca’s second division team, had answered my questions on the University during the Impact's Monday training session at the Estadio Hidalgo, but had given no word about a tour. I had resigned myself to the idea of not getting to see the facilities.

The next day, at the team hotel, I bumped into Johnathan after the Impact’s 2-2 draw with Pachuca. I can’t help but tease him: the Pachuca employee has swapped his club polo for an Impact tracksuit. To his credit, he laughs it off, and I thank him again for his help with my report. His answer takes me aback.

“How would you like to come to the University tomorrow?”

Er, I don’t know. Is mezcal tasty? (It is.)

Hours later, I would be blown away.

After a 15-minute drive uphill to the campus and the mandatory stop at security, Jorge Fonseca, promotion supervisor at the University, greets us warmly – even Johnathan, who dares showing up still clad in Impact colors. Standing up in the office he shares with a couple of colleagues, Fonseca proudly describes the facilities we are about to tour.

“We’ve built a 25-hectare campus,” he tells us. “We’re about to expand. We’re going to build 10 more fields here, and they’ll all meet FIFA standards.”

The University is one of the many properties of Grupo Pachuca, who also own several soccer clubs including two in Liga MX (Pachuca and León), the FIFA-backed Hall of Fame in Pachuca and the Estadio Hidalgo, among other things. Opened in November 2001, the campus serves many purposes: education, of course, but also administration, training, player development, accommodation, rehabilitation.

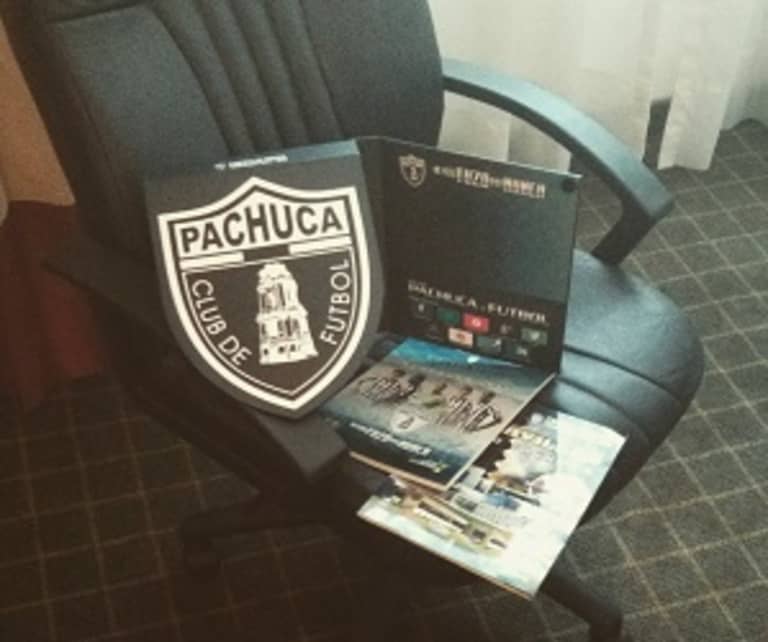

Pachuca, the soccer club, has offices on the campus. That’s where Fonseca takes us first. In the lobby is displayed the largest club crest I’ve seen in a long time. On the left is a studio where the club film their TV show for Fox Deportes, and on the right rest the Pachuca first team’s silverware.

“Here’s hoping that another of these lands here soon,” Fonseca says, pointing the CCL trophy won in 2010.

As we leave the building, Fonseca mentions the grass that has been laid all over the campus, noting that every blade has been imported from Canada. Pachuca’s climate is unpredictable – it snowed a month ago, and yet I am currently cursing my failure to apply the sunscreen I stole from my daughter when I left home. Canadian grass withstands the variations in temperature. Oddly enough, it makes me feel a tad proud of our natural resources.

And then, the University trolls me.

The previous day, my report on Pachuca’s soccer history was published. I’d written this midway through: “Some say soccer is an art. Some say soccer is a science. Some say it’s neither. In Pachuca, it’s treated as a science – an important one. The city is home to the University of Soccer and Sports Sciences.”

But as I read the bold letters on the exterior of the three-story building in front of me, I want to crawl under the Canadian grass.

A-R-T.

Oops.

Thankfully, Johnathan reassures me. “ART stands for Alto Rendimiento Tuzo,” he says. Tuzo High Performance. Phew. It’s a science after all.

Scientists leave nothing to chance, and the same applies here. The ART building is the Pachuca youngsters’ home, where up to 400 of them stay all year long, holidays aside, since its opening in 2008.

“But we actually have 1,000 students. For young kids of 9, 10, 11 years of age, it's really tough to leave their families,” Fonseca says. “So the family moves to Pachuca if needed, and we work with clubs where the kids will find a good level of competition.”

Later on, they’ll move into the ART building.

Fonseca leads us to the cafeteria. Before the kids even realize what’s on the menu, they must place their index finger on a device that reads their fingerprints and lets the staff know who is coming. The serving will vary depending on the individual’s health.

The good people working at the laundry service keep a record of which pupil drops which items, and how frequent. Officials can thus find out whose hygiene is deficient.

The youngsters quite simply have everything they need under one roof, including a 24/7 medical center. Heck, there’s even a barber shop in the basement, next door to the chapel.

I can’t help but wonder how this compares to Barcelona’s youth academy, the one every other academy is compared to these days, it seems. The main difference, Fonseca says, rests in Barça’s total focus on the sporting aspect of the young player’s development.

“We’re looking at the integral development of the athlete. Of course, we focus on sport, but we’re also developing the athlete from an academic point of view. We’re developing the human being. We supervise him medically. We monitor his rest.”

The University offers academic programs from the elementary level to the Ph.D. level – all of them on this very campus. And it’s not just for soccer players, either. Minutes later, we would bump into Carolina Luque, a student at the University and one of the top 30 female racquetball players in the world.

Pachuca want to keep building their roster with their youth academy. But should a player not make it to the professional ranks, university-level classes in fields such as administration, physical education and nutrition will prepare them for a job in the soccer industry. That’s what happened to Johnathan De Oliveira: though he’s already got his fitness coaching job, he’s still a University student in this discipline.

On the way to our next stop, we walk past a café that is being rebuilt; its roof collapsed under ice and snow not long ago. Looks like some architects took a more artistic, less scientific approach to their work.

Next up is the Joseph Blatter Building, another reminder that, well, FIFA likes this city.

The 70,000 square-foot building named after the FIFA president is what the youngsters are gunning for: Pachuca first team’s facilities. We get to see the whole thing, except the locker room. Again, nothing is left to chance. The room closest to the entrance is the senior team’s state-of-the-art – or is it state-of-the-science? – fitness center.

“Every player has a USB flash drive that he plugs into the exercise machines,” Fonseca says as first team player Diego De Buen looks on. “The fitness coach enters the training regimen of each individual player on their flash drive. At the end of the session, the players hands his flash drive to the coach, who looks over the information that was gathered during the workout.”

Should a player get injured, there’s no need to call an ambulance. The building is home to Pachuca’s High Altitude Medical Centre of Excellence, sanctioned by FIFA – them again. Even surgery isn’t off limits here. This is where Pachuca’s Argentine forward Dario Cvitanich got his knee fixed in January.

The youngsters have everything they need close by. The first-teamers have all that, and then some. Sitting on one of the leather couches in the movie theater, I’m thinking I could stay here all day. Chances are I’d tell myself the same thing if I were allowed to enjoy the press room, the massage tables or the spa.

But check-out time at the hotel is coming fast, and it’s almost time to return to the city center. Fonseca gives us magnificent Pachuca press guides, and before we leave, it’s his turn to ask a question: “Did you enjoy the tour?”

Er, I don’t know. Is mezcal tasty?