CHESTER, Pa. – There were times, Bob Hackworth remembers, when he would get lost. The woods of North Carolina were tricky that way, even if he and his family spent many summers there exploring the great outdoors. Luckily, whenever he didn’t know how to get back to the house, he could always count on one of his children to lead the way.

Young John Hackworth was the family’s very own Magellan.

“It was kind of a joke among the family,” Bob says, “that John just always knew where he was.”

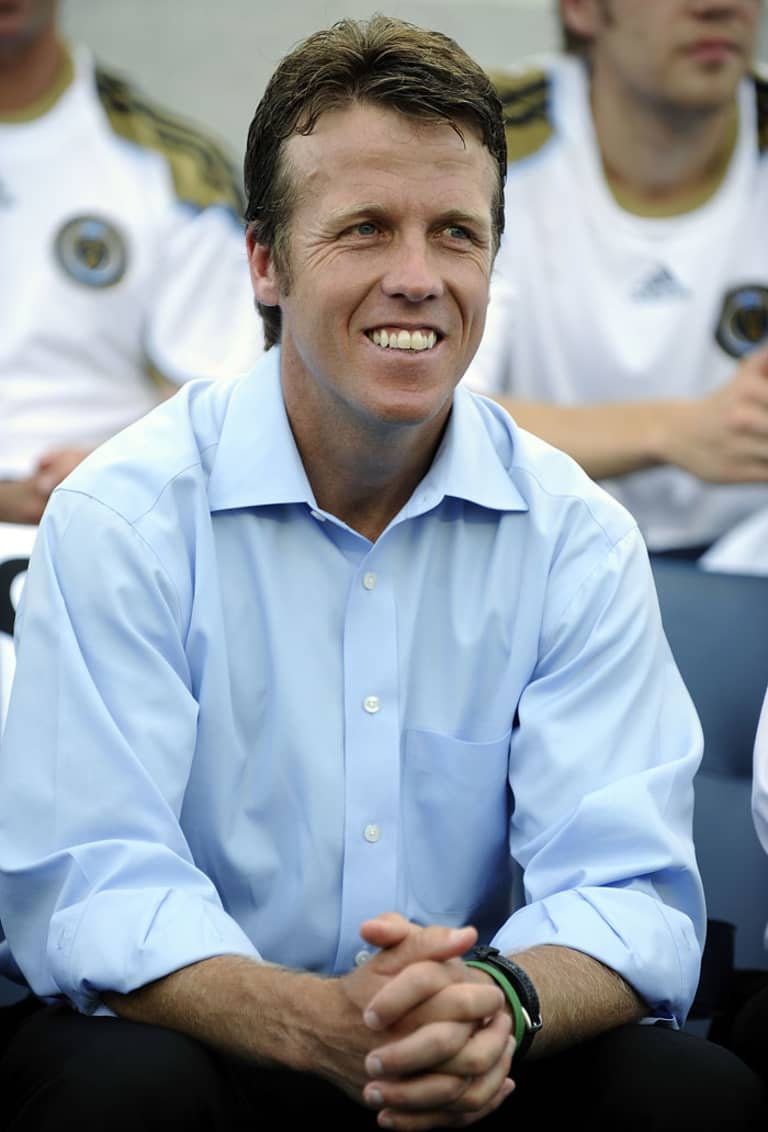

Through the next four decades, it’s a trait that never left John Hackworth. It’s how he accomplished his dream of playing college soccer in the ACC, even if it happened three years after he graduated high school … and how he became a Division I college head coach before he turned 30 … and how he shot through the coaching ranks with the US national team … and, most recently, how he was put in charge of his own Major League Soccer team.

He always knew where he was and he always knew where he wanted to go, even if sometimes the career choices he made befuddled those that knew him best.

Yes, his knowledge for the sport and his terrific people skills helped pave the path for him to become interim manager of the Philadelphia Union, a job he took over last month after the sudden dismissal of embattled ex-manager Peter Nowak. And that knowledge and those skills have helped the once-left-for-dead club revive their season heading into the midseason break represented by Wednesday’s MLS All-Star Game at PPL Park (8:30 pm ET, ESPN2, TeleFutura, TSN/RDS in Canada), where Hackworth will serve as an assistant coach for the MLS All-Stars.

But it’s also been his instinctual sense to make the right turns in life that got him to this point – instincts that began when he was as a young boy in a grownup suit, whether walking in the woods or running on a soccer field.

Athletic roots

When it came to playing sports, Hackworth, it seems, never had much of a choice. His grandfather, Clarence Barnes, was a leather-helmet football player in the old three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust NFL. His older brother, Bob Hackworth, was a collegiate cross country runner and a professional cyclist. His dad, who’s now 80, still plays tennis at least three times a week. He even grew up in the same central Florida town where the Toronto Blue Jays play their Spring Training games.

Luckily, he embraced his athletic roots and surroundings from a young age, playing baseball and soccer and running track throughout his childhood and into high school, where, he says, “I don’t remember a day where I didn’t have a training session.”

It was soccer, though, that stuck more than the other sports. As a young boy, Hackworth remembers sitting in the very top row of since-demolished Tampa Stadium to watch his hometown Tampa Bay Rowdies of the old North American Soccer League take on Pelé and the New York Cosmos in 1977. He was hooked. It was around that same time that Hackworth began to play competitive soccer, and his father remembers him being different from all of the other six-year-olds.

“When kids first learn to play soccer, most of them just run around chasing the ball,” Bob says. “John was not like that. He knew where he was and he understood where everyone else was supposed to be. And he’s been that way about everything ever since.”

Because he wasn’t a natural superstar and was driven mostly by his smarts and competitiveness, Hackworth wasn’t heavily recruited out of high school. But instead of settling on a smaller college where he could play right away, he kept his grand vision of playing ACC soccer alive, enrolling in a two-year school called Brevard College with the intention of transferring.

“I had the opportunity to go to a four-year school but teammates of mine were going to places like Clemson, Duke and Wake Forest, and I felt like I was as good as them,” says Hackworth, who’s remained very athletic and competitive into his 40s. “I just had to prove it. This was my opportunity to prove it.”

It worked out, with Hackworth using up his final two years of NCAA eligibility at Wake Forest and then springboarding that into a modest professional career with the Cleveland Crunch and the Carolina Dynamo in the early to mid-90s. Mostly used as a defender and sometimes as a midfielder, Hackworth worked hard to become a solid pro, and he says today that he might have even been able to play in MLS if it existed then.

But MLS didn’t exist when Hackworth was getting his professional start and the tiny salaries in the lower-tier leagues forced the young player to forge a new path.

“I wanted to be a soccer player,” Hackworth says, “but I also had to think about what I wanted to do with my life.”

Soon enough, it would be revealed to him.

Becoming a coach

It’s not very often when someone can point to one event and call it, unequivocally, a “life-changing moment.” Hackworth can. He remembers the moment well because it was one of the saddest days of his life. It was also the day his idol, Walt Chyzowych, died.

Chyzowych was more than just Hackworth’s college coach at Wake Forest. A member of the National Soccer Hall of Fame and a longtime Philadelphia resident, Chyzowych shaped the sport in this country as few people have, playing and coaching for the US national team, among other stops in his prosperous career.

For Hackworth, he was almost larger than life. So when Chyzowych asked his pupil, just after Hackworth graduated in 1993, to be an assistant coach for the burgeoning women’s soccer program at Wake Forest, he agreed.

At the time, coaching the Wake Forest women was a part-time job to fill the hours between playing. Hackworth still had visions of going to medical school or studying to become a physician’s assistant. But when Chyzowych died a year later – suddenly, of a heart attack, on Sept. 2, 1994 – Hackworth decided to honor his college coach by trying to be just like him.

“He believed in me and he was this icon of coaching in the U.S.,” he said. “He developed coaching schools and licensing programs for coaches in this country. … At that point, I decided – you know what? – I’m going to change directions here. I’m going to be a coach.”

After Chyzowych’s death left a giant hole in the Wake Forest coaching staff, Hackworth moved over to be an assistant with the Demon Deacon men in 1994, all while continuing to play professionally. Four years after that, he become the head coach at South Florida.

Although it wasn’t easy to leave his alma mater – the first of many difficult coaching moves for him – Hackworth knew it was an opportunity too good to pass up. At 28 years old, he was in charge of his own Division I program. And he was doing it less than an hour from where he grew up.

“I remember the day I got announced [as South Florida’s head coach], it was on the front page of the sports section of the St. Petersburg Times,” he says. “And it was the same day of my 10-year high school reunion. All of my friends from high school that I hadn’t kept in great touch with got in touch with me and were like, ‘What the hell have you been doing?’”

Hackworth did well at South Florida, taking the team to two NCAA tournaments in four seasons. But the winds of change swept through again when the opportunity arose to be an assistant coach with the US U-17 residency program in nearby Bradenton, Fla.

For Hackworth, the idea of being a part of US soccer was enthralling because, as he says, “the national team in my mind, was the be all, end all.” But other people didn’t see it that way. He remembers one ACC head coach calling him to ask if he was seriously considering leaving South Florida to coach teenagers in Bradenton. When Hackworth told him that he was, he reminded Hackworth that he was a young, talented Division I college coach who was in charge of a rising program.

He told him he had job security for life. He asked him what he could possibly be thinking. He asked him if he was crazy.

Hackworth’s response was simple: “I just think I can be better.”

From the national team to MLS

Brian Maisonneuve played nine seasons with the Columbus Crew, scored a couple of goals at the 1996 Olympics and played in all three of the United States’ games at the 1998 World Cup. But when he arrived in Bradenton in 2005, the just-retired pro didn’t know a thing about coaching. He also didn’t really know too much about Hackworth, who by then had ascended to the U-17 head coaching position after serving for three years as an assistant.

But Maisonneuve was excited for his new gig on the U-17 staff, and quickly realized how fortunate he was to have a mentor in Hackworth, who he says never felt like a boss. He absorbed Hackworth’s knowledge for the game, calling him the “best technical coach when it comes to teaching” that he’s ever been around. He watched him listen carefully to other people and take everyone’s ideas to heart. They became close and so did their families.

“I’ve never heard anyone say a bad thing about him,” says Maisonneuve, now an assistant at Indiana University. “He was an excellent coach. He was a mentor to me and helped guide my path in coaching. For that opportunity he gave me, I’ll forever be grateful.”

Many other people probably feel indebted to Hackworth, including all of the young players he helped mold into stars. Not coincidentally, many of the U-17 players he coached are now with the Union, a group that includes Freddy Adu, Michael Farfan, Gabriel Farfan, Sheanon Williams and Amobi Okugo.

Hackworth ended up coaching the U-17 squad to the knockout round in the both the 2005 and 2007 U-17 World Cups, before being hired as an assistant on the full national team under then-coach Bob Bradley, whose son, Michael, he also coached at residency. Another one of the assistants on that team was Peter Nowak, who Hackworth knew from the years when Nowak took his D.C. United teams down to Bradenton to scrimmage the U-17s.

The two grew closer on Bradley’s staff and often talked – on the plane, over breakfast, in their offices – about what it might be like to work together on something new and unique.

So when Nowak was hired to be the first manager of the expansion Philadelphia Union in 2009, he urged Hackworth to come with him to be his right-hand man. It was another tough decision for Hackworth, especially because he’d have to miss out on the 2010 World Cup. But for the fourth time in about a decade, he asked his family to trust him and went with his instincts.

“At that point, I had been with US Soccer longer than any coach at that time,” Hackworth explained. “But I hadn’t had the opportunity to be in MLS. And I knew at that point my ambition and goals were to coach in the professional ranks. And I had to learn and ply my trade a bit so I could one day be a head coach in MLS. I saw that as a much better opportunity than if I didn’t take it and if I waited to see what happened after the World Cup.”

Once again, he made the right turn.

Union head

Hackworth still won’t park in Nowak’s parking space at PPL Park and he hasn’t changed very much in Nowak’s old office, save for adding a couple of photos of his family. It’s just too weird.

He wanted this all along, to be in charge of his own professional team, to coach many of the players he knew from when they were teenagers, to make a run at an MLS Cup. He wanted to be where he was Monday, horsing around with members of the MLS All-Star Team during the team’s first practice in preparation for Wednesday’s game against Chelsea, to laugh with guys like US national team star Landon Donovan, who made sure to remind Hackworth during 5-v-2 drills that he’s getting pretty old.

But to get the job as Philadelphia Union’s manager – and subsequently as an all-star coach – at the expense of his friend and colleague?

“This is not the way I ever envisioned it happening,” Hackworth says from his new office, swiveling in his new office chair. “This is not the way I wanted to get this opportunity. Losing a friend who I respected a lot – it’s hard.”

Hackworth doesn’t like to talk about how he’s different from Nowak, and sometimes seems to cringe when he’s asked about the volatile reign of the Union’s first manager. But in his introductory press conference, he wasn’t afraid to proclaim, “I’m not Peter Nowak.”

And not long after that, he cut ties with two Nowak guys in ex-sporting director Diego Gutierrez and ex-youth technical director Alecko Eskandarian, saying, “You have to have people you have ultimate trust in.”

Looking closer, it’s not hard to see the differences between Nowak and Hackworth. Players have said it’s a more honest and open locker room with Hackworth in charge. The communication lines have been reopened with their affable and easygoing head coach, and the team seems to love that – perhaps one reason why they’ve won four of the first seven league games under their new manager to make a second-half playoff push seem like a realistic possibility.

“Players want to be taught, they want to be communicated with and they want honesty,” Hackworth says. “And that’s a really tall order when you’re trying to do that with different personalities, guys from different countries and cultures. But that’s the job. … I think that’s what the essence of being a good coach is, for what it’s worth.”

Hackworth stopped short of saying he’s a player’s coach because of the connotation that might make him look like a pushover. But if a player’s coach means he’s liked and respected by his players, well, the title fits.

“When you listen and you’re honest, players love that,” Maisonneuve says. “He is a player’s coach, and I would venture to say every player that’s played for him has really enjoyed it.”

Perhaps Hackworth’s toughest critic is the second of his three sons, Keaton. The 14-year-old has a form of autism called Asperger syndrome, which is partly why he’s not afraid to tell his father whatever’s on his mind.

“You can’t put anything past that kid,” Hackworth says. “He’s very black and white. He doesn’t sugarcoat anything. Other people tell me, ‘Hey, that was a good decision’ when maybe it wasn’t such a good decision. He’ll flat-out tell me, ‘That was not a good decision.”

Going home to hear that kind of friendly criticism from his 14-year-old – who, Hackworth says, is “surprising us every single day with the things he’s able to accomplish and do in his own life” – has really helped put the madness of the past month in perspective. And the love and support from the rest of his family has really helped too – from his wife, Tricia (who he met in his first-ever college class at Brevard) to his oldest son, Morgan (who plays in the Union academy) to his youngest son Larsen (who proudly owns the title of the Union’s “assistant to the assistant equipment manager”).

And then there’s his father, who for 40 years has marveled at how Hackworth has always managed to find the right path in the darkness of the woods, when maybe others would have gotten lost.

“If he wants to go somewhere,” Bob Hackworth says, “he’ll probably find a way.”

Dave Zeitlin covers the Union for MLSsoccer.com. E-mail him at djzeitlin@gmail.com.