I always say that the hardest thing to do in professional sports is to put yourself in position for a sure goal. Yes, that goes against the axiom, but I’m willing to be an iconoclast on this.

So many things have to go right to get that gimme. The run has to be at the right time and in the right place. It has to beat the nearest marker and the offside trap. The pass has to be precise enough to beat the ‘keeper, soft enough to give the attacker time to get himself set and hard enough to sneak past the defense.

Forget hitting a baseball. Getting a tap-in is the hardest thing you’ll ever see in athletics. Period.

NBC Sports Preview: SEA vs HOU

And some guys seem to find those chances more than others. It’s a skill set in and of itself, which is why Jozy Altidore is better at setting up goals than scoring them on the national team, for example. It takes brains, quickness, speed, strength and instincts, and if you’re off on just one of those – for Jozy, it’s “instincts” – you won’t get many chances to walk the ball into the net.

It’s an incredibly rare combination of traits, which is why teams are always willing to spend $20 million or more on a goalscorer.

OPTA has a way of measuring these chances, which they’ve appropriately labeled “Big Chances.” They’re defined thusly:

“A situation where a player should reasonably be expected to score usually in a one-on-one scenario or from very close range.”

In MLS, it turns out, teams do not finish their big chances at a very high percentage – just 317 of 766 overall. In the words of Ben Jata, who you may know better as @OptaJack: “For a professional player to only bag 41 percent of his ‘big chances,’ either the striker is doing something wrong or the 'keeper is doing something right.”

Even so, if you’re a striker who finds those chances, you’ll be valuable even if you convert at a less-than-stellar rate.

To wit, over each of the past two seasons a striker has come out of nowhere to notch double-digit goals. In 2010, it was Chris Wondolowski; in 2011, Dominic Oduro. It just so happens that, last season, Oduro and Wondo were No. 1 and No. 2 in the league in finding big chances.

So they may have been no names, but it’s pretty obvious as to why they became valuable goalscorers. Even with their low conversion rates – Oduro buried just seven of his 19 big chances, while Wondo went five for 16 – they were still finding quality looks other strikers just don’t see.

David Estrada is not one of those guys. He sees them just fine.

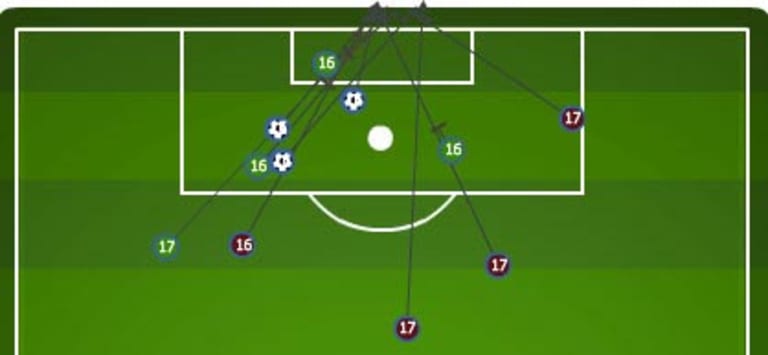

SHOT CHART: Estrada and Montero

The little Seattle forward has four goals in three games across all competitions thus far, and the reason is he’s getting into the box and finishing his big chances. Back post header? Check. Breakaway? Check. Scrum in the box? Check.

(For what it’s worth, in the preseason I predicted that Tommy Heinemann would be this year’s Oduro or Wondolowski – the guy who comes out of nowhere and scores double-digit goals. I based this upon my perception that Heinemann often put himself into position to score, but just wasn’t quite clinical enough. Turns out my instincts were mostly right – he found a big chance once every 220 minutes, a solid rate, but went 0-for-6. So yeah, he wasn’t a bad bet, but I’d like to shift all my money to Estrada now.)

With Seattle’s ability to generate those chances – they made 54 in 2011, best in the league – all that they’ve been looking for is a striker who knows how to get onto the end of them. In Estrada, they very probably have that.

Just look at his shot chart from the 3-1 victory against Toronto from last week. He’s up there alongside Fredy Montero, and if you’ll notice, everything from the Colombian DP happens outside the area or from a tight angle. Want to know why he’s a streaky player? Because he simply doesn’t find those tap-ins and breakaways that guys like Estrada, Wondolowski and Oduro manage.

Of course, there's all that free space to run into and all those distracted defenders to run past because Estrada gets to play around guys like Montero, Álvaro Fernández and Mauro Rosales.

But so did Nate Jaqua. So did Mike Fucito. So does Roger Levesque. And none of those guys found the gimmes that Estrada has turned into his bread and butter in three short weeks.

Because it really is the hardest thing to do in sports.

<p><a href="http://bit.ly/A1JslX">Get more analysis from the Armchair Analyst</a></p>