Landon Donovan first began hearing the rumors during the fall of 2001. But he didn’t think to ask many questions about what might come next.

Donovan was only 19 years old during perhaps the roughest patch in the history of Major League Soccer, and he was admittedly naive. In his first full season in the league he was focused primarily on what he could do on the field for the San Jose Earthquakes, not easing anxieties in the boardroom.

The older players were talking, that’s all Donovan knew. Word was circulating around the Earthquakes locker room that the club was struggling, and in desperate need of a lifeline that was not necessarily coming. On the field the Quakes were good — they finished second in the Western Conference during the regular season behind Donovan’s seven goals and 10 assists — but they were abysmal at the gates. Even during an era when MLS attendance expectations were modest, the Quakes averaged a league-low 9,635 fans per game.

Some pegged the Earthquakes for relocation. Others feared something worse.

"We knew we had to get into the playoffs. And the thought was that if we won, it would be really difficult for the league to move a team that had just won a championship," Donovan says today. "I remember some of the veteran guys saying pretty clearly, ‘If we don’t win a championship, we’re going to get contracted.’"

In Miami, meanwhile, the Fusion were arguably more imperiled, despite a star-studded team, a dynamic coach in Ray Hudson and the inside lane to the Supporters’ Shield. But by 2001, Fusion owner and Miami businessman Ken Horowitz was looking for a way out of MLS, having paid $20 million for the expansion team in 1997 and another $5 million to renovate Lockhart Stadium in Fort Lauderdale for the team’s debut season a year later.

At the time the Fusion had the lowest corporate sponsorship revenue and fewest season tickets in the league. They averaged just under 7,500 fans per game in 2000 and by 2001 Horowitz had soured on his experience in Miami so much that he had reportedly balked at the idea of spending $16,000 to broadcast one of the Fusion’s postseason games on local television, according to the Sun-Sentinel.

"We were getting the information in drips, but we knew that whatever we had accomplished in 2001, we probably wouldn’t be able to continue with those guys another year," says Pablo Mastroeni, who starred for the Fusion during its year on the brink. "We had no idea if the league was going to continue on."

Brian McBride was on safer ground in Columbus. The Crew were owned by Lamar Hunt, an oil industry billionaire who just two years before had spent a reported $28.5 million of his own money to build the league’s first soccer-specific stadium. McBride was the face of an organization with a future, but he could see where others were struggling.

"As players we heard some of the rumors going around, and you could see it in the crowds," McBride says. "We knew which clubs were doing well and which ones weren’t."

In today's era when MLS can pocket expansion fees reportedly as high as $325 million and ultimately field 30 clubs by the dawn of 2022, it’s understandably tough for contemporary MLS fans to imagine the fragile landscape of 2001.

The league averaged more than 21,000 fans per game league wide in 2019, but two decades ago the majority of MLS teams still played in cavernous stadiums reserved for NFL teams, and some were largely empty for MLS games. In 2001, the league averaged slightly under 15,000 fans per game, and the year before, three clubs — Miami, Kansas City and Tampa Bay — struggled to even pull 10,000 a game.

There were no youth academies or reserve league teams. There were no teams in Canada or the Pacific Northwest. The now-defunct Fox Soccer Channel — a go-to cable destination for soccer fans which showcased soccer throughout the world and even ran reruns of "Dream Team," a British soap opera based on a fictional soccer team — didn’t carry MLS games.

The league hemorrhaged money, reportedly as much as $250 million over its first six years of existence. Even some of the league’s staunchest supporters — including the original investors Hunt, Phil Anschutz and Robert Kraft — winced at the idea of staying the course and losing even more money without making significant changes.

The majority of MLS players, however, never knew most of this. Some of them, as their playing days ended and they took managerial or front office jobs, began to hear stories of how precarious the situation became. But upon being informed that in 2001 a league executive cautiously drafted a press release for a doomsday scenario of the league folding, for example, McBride audibly gasped.

"Wow," McBride said after a long pause. "I don’t think any of the players ever thought that the league would fail."

Said Donovan: "Fortunately, ignorance was bliss."

"The most important meeting in the history of the league"

Donovan and the Earthquakes ended up making that fairytale run to the MLS Cup title on Oct. 21, 2001, and a little more than two months later he was back on the field in Claremont, Calif. to open 2002. He was one of 28 players selected to the U.S. national team’s January camp, along with McBride, Mastroeni and 23 other MLS-based players.

The camp was the first of a pivotal year for the USMNT and head coach Bruce Arena. They would compete in a rare winter edition of the CONCACAF Gold Cup in February and then the FIFA World Cup in South Korea and Japan that summer, the most critical test for the program since a much different generation of American players crashed out of the 1998 World Cup in France after losing all three group games.

It was during that January 2002 camp, however, that the MLS players first got a glimpse of the ground shifting dramatically in their domestic league. On Jan. 9, MLS officially announced it was contracting both the Miami Fusion and the Tampa Bay Mutiny and that each team’s players would be reassigned to other clubs via a dispersal draft later in the month. Back in October 2001 the Earthquakes had beaten the Fusion in the MLS postseason in what was effectively the last gasp for soccer in South Florida.

The move whittled the league down to 10 teams, left MLS without a footprint in the country’s fourth-most populated state, and left Mastroeni uncertain about his future.

"A month before the US camp I was sitting there wondering what I was going to do with my stuff. We were in complete limbo," Mastroeni said. "How do we get to the next team? Are we going to stay in this league? Then we learned about the dispersal draft, but we still didn’t know what would happen next."

The contraction of Tampa Bay and Miami traced back nearly a year before the announcement was made, to a business meeting hosted at one of the oldest cattle ranches in Colorado. The sprawling, 35,000-acre belonged to Anschutz, who would sometimes welcome MLS executives and fellow investors to discuss business and the future of the league.

Few gatherings loom larger in MLS lore than the one on Dec. 11, 2000. MLS Commissioner Don Garber has since called it "probably the most important meeting in the history of the league," and Mark Noonan, who then served as the Executive Vice President of Marketing for MLS, remembers a level of urgency he never saw again during his five years working with the league.

"We didn’t even take a tour of the ranch," Noonan said with a laugh. "We flew in from New York, and it was straight to business."

Garber and MLS President Mark Abbott presented a five-year forecast that laid out a simple, sobering truth: For the league to survive into the future, the owners needed to invest even more than they already had. All 12 of the MLS clubs were losing money, and the league still owned and operated two clubs in 2000 — Tampa Bay and Dallas. Those clubs were struggling mightily, and served as a lingering sign that MLS still had a ways to go after an optimistic but austere beginning in 1996.

"There was a recognition that we needed to change that trajectory," Abbott says of the meeting. "We needed to have a different plan if MLS was going to work in the long-term."

Perhaps the biggest change involved the league-owned teams. There were no viable owners interested in taking over the league-owned clubs and it was clear that some combination of the existing group — Anschutz, Hunt and Boston-based billionaire businessman Robert Kraft — would likely have to take those clubs on financially for them to succeed.

There was also a growing crisis of awareness. In the majority of MLS markets the attendance and television ratings had been disappointing over the first five years, and despite an existing television contract with ESPN, MLS highlights were exceedingly rare on "SportsCenter," the network’s flagship nightly program.

"At that time you would still hear anchors mispronounce players’ names, or they would joke about 0-0 ties on the air," said Noonan, who oversaw the league’s media and public relations departments. "And from a press standpoint, it was hand-to-hand combat. No one was calling me up everyday and saying, ‘We want to write a big story about MLS.’"

Despite the league’s troubles, Garber and the MLS executives knew that an audience for soccer existed in the United States, based on three key data points: The reception of the 1999 FIFA Women’s World Cup held on U.S. soil, consistently robust youth participation rates in the sport and changing demographics in the country that skewed more Latino, and potentially more soccer-friendly. The group knew they needed a broader marketing strategy to reach those potential MLS fans, and during the meeting Garber pitched the idea of using the 2002 World Cup as a platform to reach them.

In stark contrast to how valuable such rights to the World Cup are now, in December 2000 there was still no one interested in acquiring the English-language rights in the United States for the 2002 World Cup.

Part of the problem was undeniably the timing — many of the games played in Japan and South Korea would be broadcast in the middle of the night or in the early morning hours in the United States, all but guaranteeing low ratings and modest returns for advertisers at best.

Although Univision would eventually purchase the Spanish-language rights, there was no guarantee the tournament would even be broadcast in English in the U.S, which would have been a devastating blow to the league.

"That wasn’t going to be a good thing for what we were trying to do," Abbott said, "which was build Major League Soccer and soccer in this country."

Garber pitched the idea that if the league bought the television rights to both the 2002 and 2006 World Cups (the events are typically sold in pairs), it could then do a production deal with ESPN and ABC, and promote MLS extensively during the programming. If the networks wouldn’t organically shine a light on MLS during one of its darkest hours, perhaps MLS investors could foot the bill and ensure the league received the exposure.

“The message was, if you’re not writing a check, you’re not going to be at this table”

Garber simultaneously raised the concept of creating a separate company to raise the commercial value of soccer in America, and grow the fanbase for the sport. The organization — which in the months following would be named Soccer United Marketing (SUM) and would begin staffing up at the league’s New York City offices — would eventually sign deals with U.S. Soccer, CONCACAF and the Mexican Football Federation (FMF) to promote each organization’s games in the United States.

"You have to remember that at that time in the United States, sponsors and broadcasters saw little to no value in our sport, as evidenced by low sponsorship and broadcast revenues for MLS, U.S. Soccer, FIFA, etc.," Garber told

Sports Illustrated in 2018. "For MLS and every other soccer property in the country to succeed, we needed to change that, and it became a major focus."

But all of that was just speculative in late 2000, and much of it hinged on whether the owners would, as Garber put it, "double down" on their investment. At one point during the meeting the three owners in the room — Anschutz, Hunt and Jonathan Kraft, who co-owned the New England Revolution with his father, Robert — asked everyone else to step out of the room so they could privately discuss the ideas Garber and Abbott had put forward.

"They said, ‘Why don’t you guys step out?’" Abbott recalled. "And that was the only time that ever happened."

Said Noonan: "The message was, if you’re not writing a check, you’re not going to be at this table."

The owners ultimately decided to financially back Garber’s plans to build the foundations for SUM and begin pursuing the television rights for the 2002 and 2006 World Cups. It would eventually cost the owners $40 million for the television rights and another $30 million to cover unilateral production for ESPN and ABC, a number that with inflation comes to roughly $103 million today. In contrast, Fox paid a reported $425 million for the rights to the 2018 and 2022 World Cups in 2011.

"It was an amazing opportunity," Abbott said. "That was a really important idea for us. It was important that we had broad exposure for the U.S. national team and that we had the ability to connect the league to it."

But could the team deliver?

MLS executives have often been reluctant to tie the league’s fate directly to the success of the USMNT, but the program's failure at the 1998 World Cup in France lingered over the team’s buildup to Korea/Japan. MLS executives knew the team had a competent, MLS-experienced head coach in Arena and that a wealth of MLS players would feature on the team, but another disappointing, early exit from the tournament would be a major setback.

"If the $40 million bet on the television rights and the creation of SUM fell flat on its face … and the [U.S. team] didn’t perform well?" Noonan said. "I’m not sure we’re having this conversation."

"You are a new breed. You welcome the pressure."

The USMNT learned on Dec. 1, 2001 that if they were to have any success at the 2002 World Cup, it would be against decidedly long odds. The Americans were drawn into Group D with Poland, host South Korea, and their opponent for the first match of the tournament on June 5, Portugal.

Highlighted by reigning FIFA World Player of the Year Luis Figo, Portugal’s famed "Golden Generation" of players made them not just the group favorites, but a legitimate challenger to win the tournament over traditional powers Brazil, Germany and France, the 1998 champion.

The Americans, meanwhile, were in a transitional period following their flameout in France, and many of the prominent players who had appeared in the previous two World Cup cycles had been phased out of the program. The team also had a leader in Arena who, after replacing embattled head coach Steve Sampson in October 1998, almost immediately imparted what McBride called a "major cultural shift" on the program.

"Bruce came in and said, ‘This program doesn’t believe. If we get a point or a draw, that’s okay. And that’s no longer the case,’" McBride said. "The first training session after we learned about the [World Cup] draw, Bruce walks in and the first thing he says is, ‘We’re going to beat Portugal.’ I still get the chills thinking about that today."

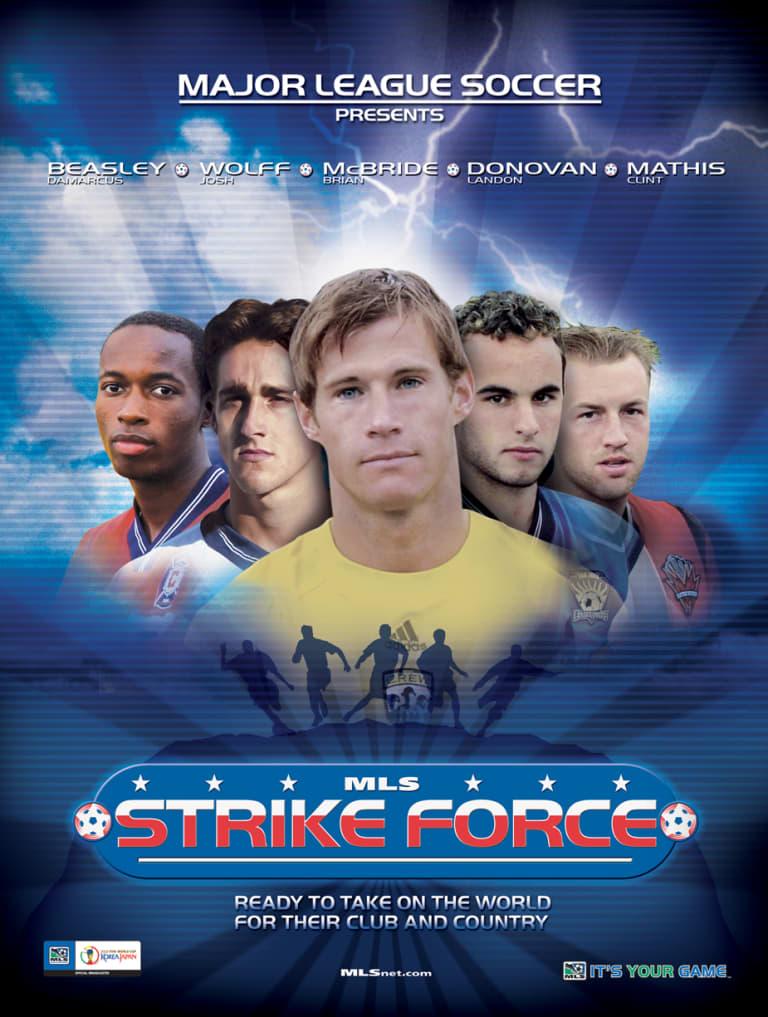

By March 2002 the Americans had won the CONCACAF Gold Cup and Arena was zeroing in on his potential World Cup roster, which promised to be a combination of MLS-based players and their peers playing in Europe. There was a noticeable indication that this team would skew slightly younger — Donovan was 20 years old and Chicago Fire winger DaMarcus Beasley was only 19, and both were in serious contention to make Arena’s final roster — and that some of the group’s best attacking talent would hail from MLS. The focal point was the 29-year-old McBride, but mercurial forward Clint Mathis had been instrumental in helping the team in qualifying, and emerged as an MLS star with the New York/New Jersey MetroStars after scoring 13 goals and adding 13 assists in 2000.

In MLS’s New York offices, meanwhile, Noonan and MLS creative director Rich Levy had been tasked with an expansive marketing campaign to promote players like McBride and Mathis and capitalize on what they hoped would be unprecedented exposure for the league.

By that time MLS was on dramatically more secure footing than just five months before. Contracting the two Florida teams was certainly a public relations bruise, but Anschutz had stepped forward to buy the MetroStars when the club’s co-owners John Kluge and Stuart Subotnick wanted out in November 2001. Anschutz had also picked up San Jose and Hunt took over in Dallas, and the league had also secured the television rights for the World Cup and partnered with ESPN and ABC for the production.

Levy was a film buff who long admired the promotional movie posters from 1970s sci-fi releases like "Bladerunner," "Rollerball" and the early "Star Wars" films, and he saw the World Cup campaign as a perfect instance to pay homage to the artwork he adored. When he met with Noonan in March 2002 to begin work on the campaign he gravitated almost immediately to a similarly sci-fi aesthetic, with dramatic, heroic images of the key MLS stars front and center.

"It was a great opportunity," said Levy, who went on to design a variety of MLS team logos as well as the Philip F. Anschutz MLS Cup trophy. "We wanted to plant the seeds that the players from the U.S. team were coming from MLS, and they would be on the biggest stage in the world."

Said Noonan: "We wanted to highlight the offensive players, and the good news was that the guys who were going to get the goals, those were our guys."

Though it was unclear in March which players would ultimately make the roster — let alone play in June — Levy settled on the idea of five players in the composition, with McBride featured most prominently, flanked by four others. By that point Donovan, Mathis and Beasley seemed like safe bets for the campaign, but the fifth player remained something of a gamble.

Levy entertained the idea of Los Angeles Galaxy veteran and 1990s-era USMNT hero Cobi Jones, as well as rugged Chicago Fire midfielder Chris Armas. Levy also had a folder of images on file for Mastroeni, who had landed in Colorado after the Fusion dissolved.

MLS lacked a variety of analytics back then to accurately judge how various players resonated with fans. Levy couldn’t pick a player based on page views or video views on the league’s website, or social media followers. And although the league debuted on EA Sports’ popular FIFA video game series in 2000, there wasn’t enough reliable data to influence Levy’s decision.

In the end, Levy went with his instincts — and which players were most popular among fans in the MLS Yahoo Fantasy League.

"Josh Wolff was lighting it up back then on fantasy in terms of fan usage rates, and that was our rationale," Levy said. "No one could deny what he was doing, so we went with our gut."

Despite the almost arbitrary selection criteria, Wolff’s credentials were solid. A quick and dangerous second forward from the Chicago Fire, Wolff emerged as a hero in February 2001 during the USMNT’s 2-0 World Cup qualifying win over Mexico in frigid conditions in Columbus, scoring a goal and adding an assist off the bench in what is now affectionately known as La Guerra Fria ("The Cold War").

Noonan and Levy eventually coined the campaign "MLS Strike Force," added a tagline reading "Ready to Take On the World For Club and Country," and it was off and running. What followed was a marketing blitz that highlighted the group of MLS players on posters, hats, T-shirts and television advertising spots, the last of which interspersed game highlights with slo-motion glances at the camera and a not-so-subtle script.

"You are a new breed. You welcome the pressure," says the anonymous female narrator, channeling a futuristic, robotic monotone. "You are Major League Soccer's Strike Force."

Arena released his 23-man World Cup roster on April 22, with all five of MLS’s poster boys in tow, along with six other MLS players: Armas, Jones, Mastroeni, San Jose defender Jeff Agoos, D.C. United defender Eddie Pope, New England defender Carlos Llamosa and Kansas City goalkeeper Tony Meola.

The USMNT opened World Cup training on May 1 in Cary, N.C., and left for Seoul, South Korea on May 23.

"We're not going to win [the World Cup] because we're not a good enough team," Arena said before the tournament began. "I don't think anyone is going to be damaged by us saying that. I mean, how many countries have won it? If we can get a point in the first game, it will put the whole group in chaos."

"We were a little league still growing, but we were proud of where we came from."

Although Arena’s team featured 10 players who had also featured for the USMNT during its disastrous previous run at the World Cup in France, the message was clear almost immediately: There would be no such drama this time around.

One of the signature calling cards over the course of Arena’s stellar career has been his ability to not just develop a collective team personality for his clubs, but to allow each individual player’s personality room to breathe. He cultivated an ethos on the 2002 team that encouraged the veteran players to take on roles of responsibility while allowing a fearless crop of young players to flourish without unnecessary pressure.

"The chemistry on that team was different from every other World Cup squad I was with," said Beasley, who went on to play in four World Cups, more than any other player in USMNT history. "We had a lot of different personalities, and Bruce wasn’t afraid to let guys show those personalities off the field. You can’t do that in every situation and it won’t work for every team, but for that 2002 team, it worked."

Agoos taught Mastroeni to play guitar. Donovan loitered in the room shared by defenders Frankie Hejduk and Gregg Berhalter, both playing in Europe. Wolff roomed with Eddie Lewis, a veteran winger who had leveraged his success in MLS to a deal with English club Fulham. Jones and veteran Earnie Stewart playfully mocked Beasley for wearing a do-rag and an earring during lunches and a televised interview on ESPN.

And assistant coach Dave Sarachan — who enjoyed years of success working with Arena internationally and in MLS — took on the role of de facto team psychologist, a sounding board for some players quietly dealing with pressure they’d never known before.

"The blend of the different groups was always there," Wolff said. "The older guys, the younger guys, the MLS guys, the European guys. There was never a separation."

There was a sense of urgency among some of the MLS players that the league was on display at the World Cup, even if MLS had been featured there before. The 1998 team boasted a number of MLS players at the time — McBride, Pope and Jones, among others — but the 2001 ownership issues and ensuing contraction had pushed the league off its expected trajectory, and the players who came up in MLS and found themselves front and center of the league’s marketing campaign felt a burden of winning back respect.

"Nobody knew about our league, nobody thought it was good, nobody thought it was competitive," Donovan said. "So to do well and show well against some of the best players in the world was absolutely a point of pride."

Said Mastroeni: "That was one of the reasons that that team’s ego was checked at the door. We were a little league still growing, but we were proud of where we came from."

The World Cup opened on May 31 in Seoul, with defending champion France playing against Senegal, a team making its first-ever appearance in the World Cup and seeded dead last among the 32 teams in the tournament. The French played without injured 1998 hero Zinedine Zidane, fell behind after 30 minutes and never recovered, losing 1-0 in front of more than 62,000 shocked fans and a world watching on television.

Five days later the U.S. finally opened the tournament against Portugal in Suwon, South Korea, the 32nd and final game of the first slate of group matches.

"If you haven’t already seen enough evidence over the first three or four days, clearly there’s nobody favored when you step on the field," Arena told his players before the Portugal game. "When we win today I’m not going to be surprised."

Back in the United States the game kicked off at 5 a.m. in New York and 2 a.m. on the West Coast, but those who fought off exhaustion reaped the rewards. The U.S. carved out a 3-0 lead over the first 36 minutes thanks to goals from midfielder John O’Brien, McBride and a Portugal own-goal set up by Donovan, and the Americans held on for dear life over the final half hour to grab a stunning 3-2 upset.

Then they hopped on the bus, returned to the team hotel and began steeling themselves for a match against the host South Koreans five days later.

"It was like trying to hide an elephant with that haircut. We had nowhere to run."

Not long after the team first arrived in South Korea in late May, McBride noticed something different about the television commercials there. The American players split their time between workouts, meals and lengthy stretches of downtime at the hotel, often playing cards with each other or watching television.

Two of the World Cup’s biggest sponsors — Coca-Cola and Hyundai — didn’t use their time to promote their products as much as they did to rally support from the South Korean fans, who filled the streets of the country’s biggest cities and flocked to the stadiums on World Cup match days.

Even through his fruitless attempts to translate the commercials into English, McBride recognized they were primarily to teach fans choreographed songs and chants to be used at the games.

"By the time we played South Korea, every single South Korean fan knew the chants," McBride said. "That was the first and only time I’ve ever seen the whole stadium chanting the same exact thing. That atmosphere suited Clint, and I think he absolutely thrived in that situation."

Clint Mathis was already a sensation by the time the U.S. played its first game in the World Cup, and his story was well trodden. The

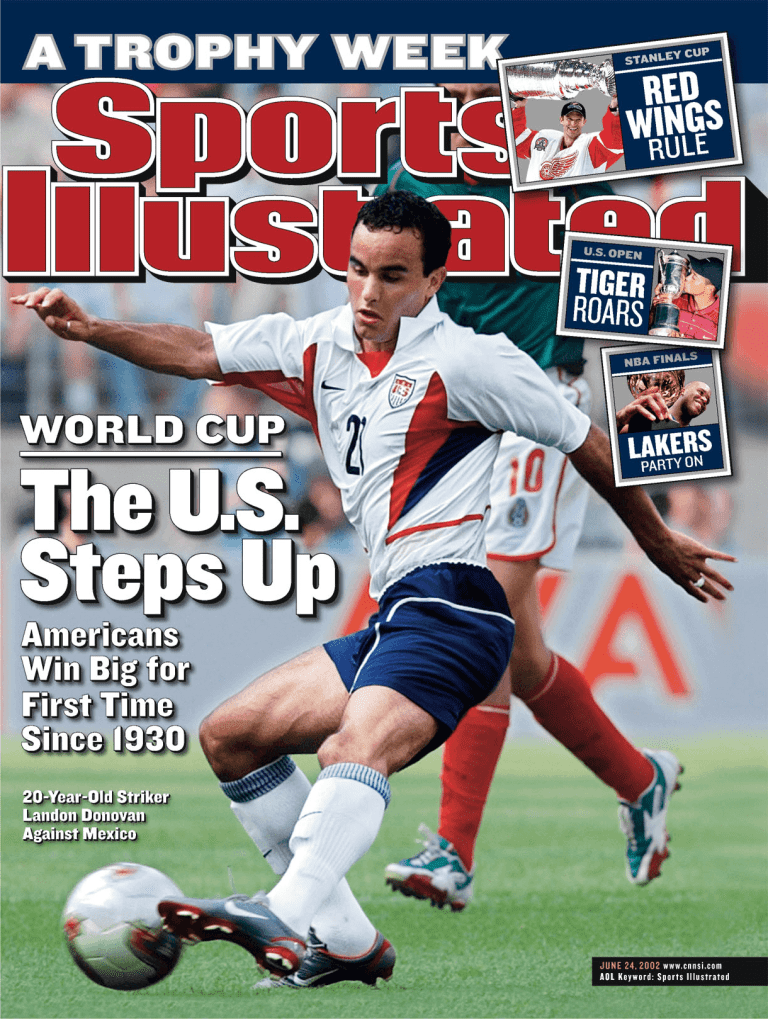

New York Times Magazine highlighted his upbringing in Conyers, Ga., and how his mother was so inexperienced with the sport when her son began playing that she wrote down 's-o-c-k-e-r’ in her date book. The Guardian called him "the first of a new breed of bona fide, US-born-and-reared soccer stars." And Sports Illustrated, which made Mathis the second USMNT player to ever grace its coveted cover just weeks before the World Cup began, detailed how earlier in the spring he had quietly flown to Germany to spend a day talking to officials from Bayern Munich about a potential transfer worth at least $5 million.

But for all the hype Mathis carried into the tournament, he didn’t play in the USMNT’s opener against Portugal, one of the biggest wins in the program’s history. So he sought counsel from Sarachan.

"He wasn’t happy and I think he wanted to vent," Sarachan said. "Honestly I think Clint went through a lot emotionally in that tournament, and he went through a lot of variations of himself."

Mathis was frustrated and restless the day before the team’s matchup against South Korea in Daegu, and he needed a change. He and Mastroeni were roommates on the trip, and after a team breakfast Mathis asked Mastroeni to cut his hair into a mohawk so that he could "have some fun, and fly off the cuff a little," according to Mathis.

Mastroeni balked at the idea and called it "totally crazy," but Mathis persisted. Eventually the two retreated to their room and Mastroeni shaved one side of Mathis’s head, and then the other. Still dealing with fatigue from workouts and travel, they eventually took a nap, only to be woken up by a phone call from team administrator Pam Perkins.

"We had overslept our alarm, and there was a team meeting. They were all wondering where we were," Mastroeni said. "The last time anyone had seen Clint he had this nice head of hair, but here we are, stumbling into the meeting and everyone is already there. It was like trying to hide an elephant with that haircut. We had nowhere to run."

Said Sarachan: "There were no words. In our minds we thought, ‘We aren’t even going to get into it with [Mathis] at this point, because there is too much at stake.’"

Mathis insists he changed his look so dramatically to help break up any tension heading into the team’s next match. After the win over Portugal, the Americans were in a surprisingly fortunate position, able to glimpse a path to the knockout round but still wary of the South Koreans, the fittest team in the World Cup and one galvanized by what felt like an entire nation in the stands.

"There was a lot of pressure going in," Mathis said. "I thought maybe I could make the guys laugh and it might take some of that pressure off. Pressure gets to a lot of athletes, and sometimes that’s when they don’t perform well. So if we could take it away, we could go out and perform."

The next day Mathis started up top and promptly scored one of the most celebrated goals in USMNT history. A streaking O’Brien delicately floated a ball over the heads of two South Korea defenders to Mathis, who corralled the ball with his right foot and buried a left-footed shot into the back of the net from 15 yards out. He stretched his arms out wide in celebration before McBride caught him near the sideline and wrapped him in a bear hug.

"I’ve never been in a stadium before or after that game that had an atmosphere like that," McBride said, "and I’ve never experienced a stadium fall silent like that."

Unfortunately for the Americans, the lead didn’t hold. South Korean forward Ahn Jung-hwan nodded home the equalizing goal in the 78th minute and the teams settled for a 1-1 draw. Arena was fuming after the final whistle that his team had wasted the Mathis goal and missed the chance to secure a spot in the knockout round, something few outside the U.S. locker room could have ever expected when the tournament began.

Sarachan and fellow U.S. assistant Glenn "Mooch" Myernick, however, wrangled Arena before he spoke to the team in the locker room to offer some perspective.

"We had to calm him down," Sarachan said. "We had to remind him what the team had actually accomplished. We didn’t tie a team. We tied a country."

"You could definitely make the argument that it helped save the league."

The USMNT’s 2002 World Cup run ended four days later in the quarterfinals in Ulsan, in a 1-0 loss to Germany. Though the Americans generated a wealth of scoring opportunities over the first half hour — "some of those chances still eat at me today," Donovan said — they fell behind on a header from German midfielder Michael Ballack off a set piece in the 39th minute, and never equalized.

The U.S. nearly scored when Berhalter skipped a volley under the outstretched arm of German goalkeeper Oliver Kahn in the 50th minute, but the Americans’ cries for a handball on the goal line by defender Torsten Frings went unheeded. Germany went on to edge South Korea in the semifinals before ultimately losing to Brazil in the final. The U.S. has never made it past the Round of 16 since.

After the quarterfinal loss the U.S. locker room was understandably sullen. They had been the better team for large stretches of the match and drew praise from the Germans for their unexpected talent and guile, but they’d also missed a golden chance to continue in the tournament.

"We weren’t outplayed," McBride said. "If that first game against Portugal game had lasted another 10 minutes, we would have been in trouble. But we all wished we could have had another 10 minutes against Germany. And I think that shows the distance we covered mentally in that tournament."

Added Donovan: "We played as well as we could have played. I still think there’s a sense of pride there, yes, that we could have won and moved on, but we also could have been knocked out of the group stage. Maybe everything evens out."

Nearly seven million people in the United States watched the U.S.-Germany game combined across all telecasts, including the live early-morning broadcast on ESPN and the replay on ABC later that day. By the time the tournament was done more than 85 million viewers had watched the World Cup in the United States.

The MLS players flew home in the days following the Germany match and were immediately embraced both by old fans and new who had just discovered them. Mastroeni was recognized in his native Arizona, and Mathis suddenly had gawkers on the streets of New York City. Beasley was greeted with a standing ovation when he returned to the Fire in July and Donovan, who had scored two goals at the World Cup before he could even legally drink champagne to celebrate, returned to find that the soccer landscape in America had completely shifted.

"Everything in my life changed," Donovan said. "All of our lives all changed, and soccer for the first time had some energy to it. The stadiums were a little fuller, the fans were a little more knowledgeable, they were a little more excited. It changed the way we were viewed and the way soccer was viewed."

"This game is going to be won by [expletive] men, not little boys."

The Americans’ run of results ended with a thud four days later in Daejeon. Poland scored twice inside the first five minutes and the Americans couldn’t make a dent until Donovan scored a consolation goal in the 83rd minute as Poland handed the U.S. a sobering 3-1 defeat.

Luckily for the U.S., South Korea toppled Portugal in their final group stage game, pushing the Americans through to the knockout round and into a fateful Round of 16 game with arch nemesis Mexico on June 17 in Jeonju.

The day before the Mexico game the team received a call from President George W. Bush — "A lot of people who didn’t know anything about soccer, like me, are excited and pulling for you," Bush told the team — and there was a quiet confidence among the Americans that they were facing a prime opportunity to make history.

After all, the Americans had won four of the previous five matches against Mexico heading into their first-ever World Cup meeting. And despite injuries and suspensions which forced minor but effective lineup shifts — playmaker Claudio Reyna slid to right midfield and Wolff earned his first World Cup start up top with McBride — the players had coalesced by that point around each other and Arena, who spared his team any subtleties before they stepped on the field.

"This game is going to be won by [expletive] men, not little boys. And we’re going to be [expletive] men today…" Arena told the team in the locker room. "Leave nothing on the field. If I have to [expletive] carry every one of you in, after 90 minutes, 120 minutes, penalty kicks, I’ll gladly do it."

What followed is the stuff of American soccer lore. In the 8th minute Reyna galloped down the right flank on a 40-yard run and threaded a pass to Wolff, who deftly one-timed a pass from the end line back into space in the box. McBride pounced with a right-footed shot into the back of the net, and the U.S. led 1-0.

"All of our lives all changed, and soccer for the first time had some energy to it."

In the 65th minute the U.S. struck again, this time off a buildup from the left side. Lewis took a diagonal ball from O’Brien and served up a cross to a streaking Donovan, who calmly nodded home a header, pushing the Americans ahead 2-0. The U.S. held on comfortably over the final 25 minutes against a frustrated Mexico team that lost defender Rafa Marquez to a red card in the 88th minute, booking the program’s first ticket to the quarterfinals since a semifinal berth in 1930.

Back in the United States the game once again kicked off in the middle of the night — the match began at 2:30 a.m on a Monday morning on the East Coast — but the television ratings were the highest they’d been for a U.S. game up to that point in the tournament. Nearly two million viewers tuned in for the English language broadcast on ESPN, and another 4.5 million people watched live on Univision or on tape delay the next morning on Telefutura.

Abbott watched the game from the den in his home in suburban Connecticut, and called Garber immediately after the final whistle to celebrate. On top of the U.S. team toppling their hated rivals to reach the final eight of the World Cup, MLS players had scored five of the team’s seven goals in the tournament.

"Not only is the U.S. team winning, but these Strike Force players are some of the ones who were doing so well," Abbott said. "I contrast that happiness to what was happening in December 2001, when there were a lot of different things we were doing at that time — things that looked like we were really in trouble. It was incredible."

Within days the group of Donovan, Jones, Mathis and forward Joe-Max Moore appeared on "The Tonight Show With Jay Leno" to discuss the win, via a remote interview from Korea.

"The country is going crazy, you guys," Leno told the group. "Landon … have you seen this yet? You’re on the cover of the new Sports Illustrated. Did you know that?"

Indeed, Sports Illustrated had put Donovan on the cover of its June 24 edition, the second time the magazine gave a U.S. player the honor in a month. Donovan and the USMNT had been selected over the Los Angeles Lakers winning the NBA title, Tiger Woods winning the U.S. Open and the Detroit Red Wings winning the Stanley Cup.

Within 18 months Fulham paid MLS a $1.5 million transfer fee for the rights to McBride, who went on to become a folk hero at London's Craven Cottage. Mathis signed with German club Hannover 96 the same month, and six months later Dutch giants PSV Eindhoven paid MLS a $2.5 million transfer fee for Beasley, who later became the first American to play in the UEFA Champions League semifinals.

Those signings continued to inspire a slew of younger Americans to venture abroad after starting out in MLS — Michael Bradley to Dutch side Heerenveen, Clint Dempsey to Fulham, Jozy Altidore to Spanish club Villarreal and Maurice Edu to Scottish side Rangers — and a number of the stars who carried the USMNT through the late 2000s and into the 2010s cite the program’s run in South Korea as the moment anything became possible for soccer in the United States.

"I’m still in touch with guys like Jozy Altidore and Maurice Edu, and sometimes it’ll come up," Beasley said. "They’ll talk about how they saw us on television in 2002. They saw guys like Landon and me at 20 years old playing in the World Cup, and said, ‘Maybe I could do that, too.’"

Said Abbott: "Who knows how many American players watched Landon and said, ‘That’s who I want to be?’"

Perhaps more tangible for MLS to measure was the immediate interest in the league from a variety of business angles. Discussions began during the World Cup for a television deal between MLS and Fox Soccer that was ultimately signed, and when the league once again began discussing expansion in the wake of their humbling 2002 contraction, there were interested parties waiting.

Noonan, who oversaw the league’s corporate partnerships, said the World Cup made it easier for MLS to continue an ongoing sponsorship deal with Pepsi, and then in October 2004 to sign a 10-year deal that made Adidas the league’s official athletic sponsor and product supplier.

"We had a proof of concept that we weren’t full of [expletive]," Noonan said of the World Cup. "We were saying it was a sport for a new America, and the world was watching, and now we had substance behind what we were saying."

Mexican businessman Jorge Vergara purchased famed Mexican club Chivas de Guadalajara in 2002 and promptly picked up on the rise of American soccer while watching the World Cup. He approached MLS executives soon after about owning an expansion team in Los Angeles, and Chivas USA opened play in 2005.

Garber and Abbott attended a sports financing conference in Florida in early 2004 and found themselves seated for dinner next to Dave Checketts, who had served as the top executive for the NBA’s New York Knicks and Utah Jazz. Checketts had seen the U.S. team at the 2002 World Cup and was interested in jumping back into professional sports, and the idea of an MLS expansion team in his native Utah piqued his interest.

"If you look at all the major leagues and their growth and development, you have to conclude that soccer is finally going to take hold in this country, mostly because of the kind of ownership that these teams have," Checketts said when Real Salt Lake was unveiled as an MLS expansion side ahead of the 2005 season. "These [owners] are guys who are pretty determined and passionate about it."

Two years later MLS expanded to Toronto and David Beckham arrived in the United States to usher in the Designated Player era. More clubs emerged and thrived in Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, and soccer-specific stadiums came to once-beleaguered markets in New York, Kansas City and San Jose. Earlier this year soccer even came back to Miami, a market where MLS had been left for dead nearly two decades ago.

"[In 2001] we didn’t have the strength, we didn’t have the capacity and we didn’t have the momentum," Garber said before Inter Miami debuted in March. "The country just wasn’t ready. Now, all of our energy is going to be focused going forward."

Now twice the age he was when he felt the league falter a bit under his feet in 2001, Donovan has a greater perspective on the precarious stretch from the winter of 2000 until the summer of 2002, when the league went from a flirtation with disaster at a conference table in Colorado to a day in the sun on the other side of the world.

"If I was an investor in the league at that time, I’m probably thinking that there’s a glimmer of hope for this league," Donovan said. "If we had crashed out of that World Cup? Maybe they would have said they had put in enough money and they tried, and simply gone their separate ways. You could definitely make the argument that it helped save the league."

Added Abbott: "To endure through all of that, it was one of the most seminal moments in league history, no question."