Editor's note: This article originally ran on June 15, 2014, ahead of the United States' World Cup return to Brazilian soil. Walter Bahr passed away on June 18, 2018 at the age of 91.

Immediately after leading the US national team to arguably the greatest upset in sports history, Walter Bahr held onto two things: the game ball and a strange feeling of guilt.

The first, he got rid off right away when Gino Gardassanich, the team’s big and imposing backup goalkeeper, took the ball from Bahr and told him that he’d make sure nobody tried to steal it as fans rushed the field to celebrate. But the second thing Bahr has never been able to shake in the 64 years since he and an unlikely band of ragtag Americans shocked mighty England, 1-0, in a group-stage game at the 1950 World Cup in Brazil.

“It’s a funny thing, but I still remember this,” says Bahr. “I was happy and enthused and whatever, but I’m not one for big celebrations. I’m sure I shook some hands and got some pats on the back. But I was thinking going to the bus that I didn’t know whether to feel happy for us or feel sad for those poor English guys. How are they going to explain a defeat to a 500-to-1 underdog?”

If anyone has ever been justified in celebrating his own accomplishments, it’s Walter Bahr. A living legend in the sport, Bahr was not only a longtime captain of the US national team but also a standout professional player in his native Philadelphia, before going on to become a successful college coach at Temple and Penn State.

But even now, as he spends most of his days playing golf or cutting grass outside his Central Pennsylvania home, the 87-year-old has trouble accepting praise for being one of the greatest American soccer figures of his generation – if not ever – and for playing a pivotal role in the historic upset that’s been portrayed and mythologized in books and on film.

“I think even if he played today, you’d never see him celebrate a goal,” says his son, Chris. “He enjoyed playing sports, and he let other people tell him if he was good.”

According to Chris, his father hardly ever mentioned the 1950 World Cup to him and his three siblings, and that they found out about it “like a lot of people – we read it in the paper, I guess.” But humble though he may be, Bahr doesn’t mind talking about the game when asked – which, in the weeks and months leading up to the first World Cup held in Brazil since 1950, has been often.

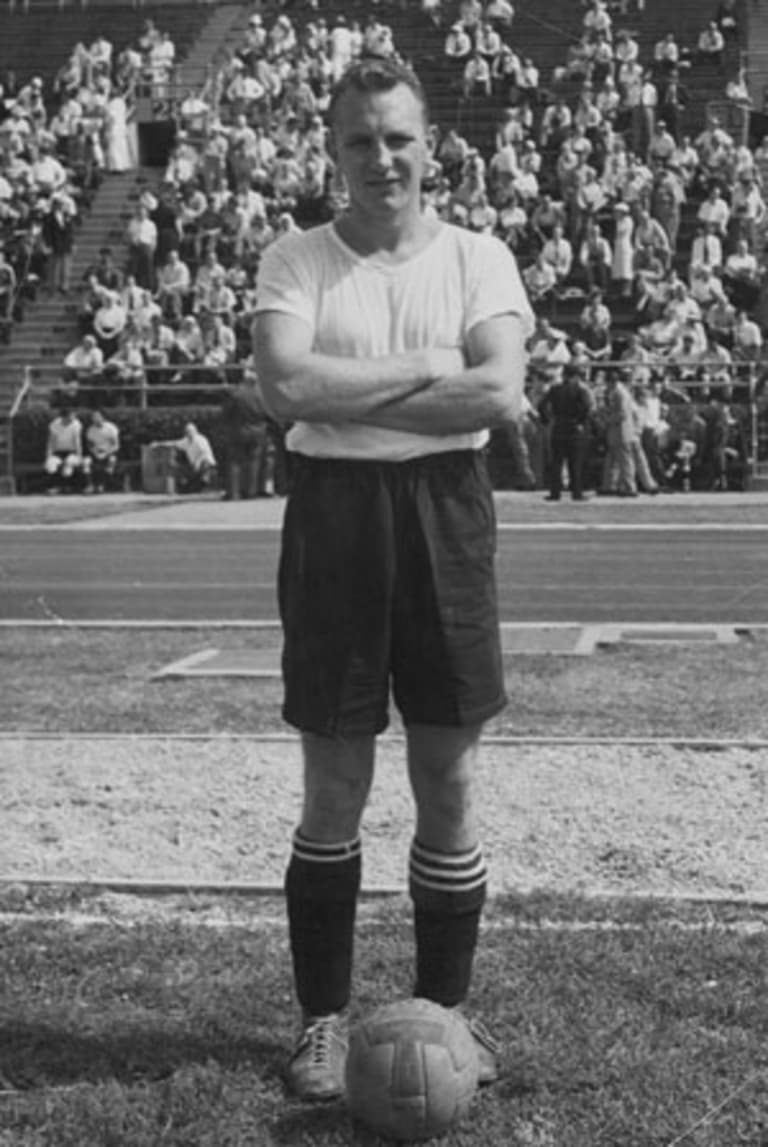

Walter Bahr in undated photo for the US national team. Bahr assisted on one of the most historic goals in the nation's history during the 1950 World Cup, but he and his teammates had no idea it would stand the test of time. (National Soccer Hall of Fame)

“The odd thing is I would guess in the first 25 years after 1950, I didn’t get two requests for an interview,” Bahr says. “But as the World Cup grew in stature, each year I would get more and more calls.”

For Bahr, one of the last living players from the 1950 team, the only issue he has with doing interviews is that the win over England is “ancient history” and that he feels like he has “nothing new to say” about it. Nevertheless, it doesn’t take long for the 87-year-old to begin eloquently recounting all of his memories from that summer in Brazil, starting with what he believed set the stage for the historic upset: the unique selection of the team.

According to Bahr, head coach Bill Jeffrey didn’t necessarily choose the best players but put a premium on chemistry by selecting a few sets of pairs that knew each other well: right wingers Frank Wallace and Gino Pariani from St. Louis, left wingers John Souza and Ed Souza (no relation) from Fall River, Massachusetts, and midfielders Bahr and Ed McIlvenny from Philadelphia.

“I think that led to us hitting it off,” Bahr says. “So many times when they have a select team, they pick what they think are the better players by reputation and so forth, but very often a team doesn’t have necessary practice time and they just don’t hit it off.”

The Americans’ chemistry became apparent when, in their first World Cup game, they held an unlikely 1-0 lead over Spain in the 80th minute before dropping a 3-1 decision. Still, that surprising performance didn’t change the sentiment that the US would get annihilated by an English team that had posted a 23-4-3 record since the end of World War II.

The USMNT, meanwhile, had lost their last seven international matches by a combined score of 45-2 and featured a squad made up of part-time players that made ends meet by working as mail carriers, dishwashers or, in Bahr’s case, teachers.

But like all huge underdogs, Bahr and company used the long odds that they faced – they were 500-to-1 to win the World Cup, while the English were 3-to-1 – as something of a motivating tool.

“That was good ammunition for us,” Bahr says. “We thought, ‘We’re not going to take a bath in this game. We’re going to give it our best.’”

Bahr (pictured here in an undated photo) says he returned to the United States following the US team's historic upset and none of the students he taught at a Philadelphia area even knew he had played the game. (National Soccer Hall of Fame)

Bahr is the first to admit the English were the better team “before, during and after” June 29, 1950 and that they simply didn’t catch any breaks, striking the woodwork a couple of times.

But as the game wore on and the US managed to keep the game scoreless, the Americans’ confidence grew, the Brazilian fans in the crowd rallied behind the underdog and, Bahr believes, the English players began to second-guess themselves.

The game’s only goal came in the 37th minute when Bahr took a long shot from about 25 yards out and Joe Gaetjens dove and redirected it past English goalkeeper Bert Williams.

Over the years, some have called the goal lucky – which really bothers Bahr because, as he puts it, “Joe was one of these guys that was a goal-scorer and I know he made an effort to get the ball.”

Says Bahr: “It was the goal of a lifetime. You just don’t know that at the time.”True to form, Bahr did not too much rejoicing after the ball went into the back of the net. He didn’t celebrate after the US survived a late English charge to pull off the massive upset, or when Brazilian fans ran onto the field and hoisted up American goalkeeper Frank Borghi, the only other player from the team that’s still alive.

And even after Bahr passed off the game ball to Gardassanich before returning to the locker room, he still didn’t celebrate.

It was hard, after all, to recognize just how big the moment was at the time, especially when the team was greeted with little fanfare and hardly any media attention when it returned to the United States following the World Cup (which ended with a 5-2 loss to Chile).

When asked what kind of response his students at John Paul Jones Junior High School (in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia) gave him upon his return, Bahr can only laugh.

“Nobody knew,” he says.

–-

Bahr (right) shakes the hand of England captain Bill Wright before a 1953 friendly at Yankee Stadium. After his career with the US national team, Bahr went on to coach in his native Philadelphia before he spent 15 years at the helm of Penn State. Two of his sons went on to become Super Bowl champions as NFL placekickers. (National Soccer Hall of Fame)

–-

But as soccer in this country has grown, so has Bahr’s legend. Given the country’s fascination with great underdog stories, it certainly makes sense. Take Bahr’s native Philly, for instance, where there’s a statue of the fictional boxer Rocky, the small guy that beat up on bigger guys in the movies.

And yet, through it all, Bahr has stayed grounded – traits he passed on to his children: sons Chris, Matt and Casey and daughter Davies Ann. Like their dad, all four were star athletes, with the three sons playing professional soccer and Chris and Matt winning Super Bowls as NFL placekickers. And like their dad, they didn’t much care for celebrations, even in the biggest moments.

According to Chris, former quarterback and famed NFL analyst Terry Bradshaw used to imitate Matt’s reaction to missing a field goal by shrugging his shoulders with his palms turned up. And then he’d imitate Matt’s reaction to making a field goal by doing the same exact thing.

Bahr presents the game ball to US Vice President Joe Biden before the Philadelphia Union's home opener at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia on April 10, 2010. (Getty Images)

Sure enough, after kicking the game-winning field goal as time expired to send the New York Giants to the 1991 Super Bowl, Matt Bahr simply shrugged his shoulders and put his palms up – before everyone mobbed him.

“That’s just how he brought us up to react to things,” Chris says of his father. “To take it in stride and move on.”Bahr’s humility comes across toward the end of his interview with MLSsoccer.com, when he makes a simple request.

“I’m going to hold you to this now,” he says. “Don’t say anything that makes England look bad. And don’t say anything that praises us too much. It was a game that was one for the books and we’re all proud of it. So don’t pump us up at the expense of the English.”

Then he pauses, and in his gravely voice, adds the lesson he and the team dubbed by one foreign newspaper as the “band of no-hopers” taught to England that day in 1950, the rallying cry for every little guy that’s ever tried to upset the big guy, the one that’s inspired so many different underdogs in so many different sports for so many years, however simple it may seem.

“I don’t know how this World Cup will turn out but I’m sure there’s going to be a couple of upsets along the way,” he says. “That’s one of the good things about sports. You have to play the games.”

Dave Zeitlin covers the Philadelphia Union for MLSsoccer.com. E-mail him at djzeitlin@gmail.com.