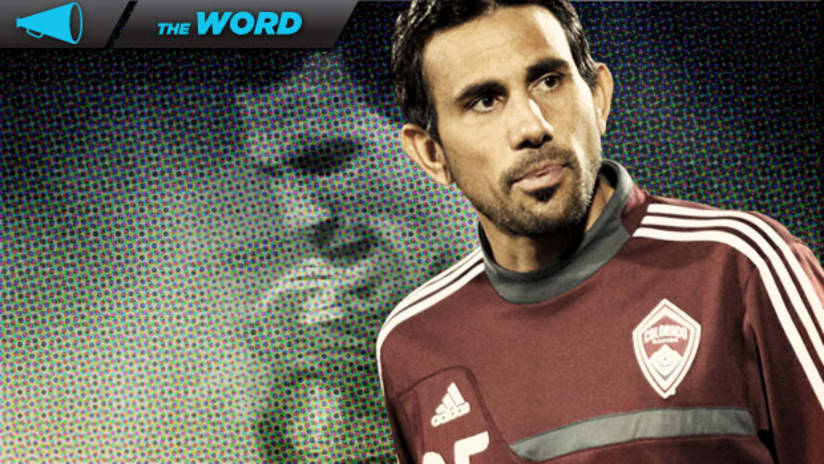

"The Word" is MLSsoccer.com's new weekly long-form series. This week, senior editor Nick Firchau looks at Colorado Rapids captain Pablo Mastroeni, who played in his first MLS game last weekend after spending nearly a year battling symptoms of a concussion. Mastroeni, who considered retirement last season because of the emotional and physical toll from the incident, will serve as the team's captain when the Rapids play in their home opener on Saturday.

Lost in the glow of Major League Soccer’s opening weekend on March 2 was the quiet return of one of the league’s all-time greats, who somehow overcame nearly 18 months fighting one of the game’s most devastating injuries.

But Pablo Mastroeni, the Colorado Rapids midfielder who last Saturday played for the first time in nearly a year after privately quitting on a 16-year professional career due to emotionally crippling concussion-related symptoms, wouldn’t have it any other way.

The way Mastroeni sees it, this moment wasn’t really for anyone else to savor anyway. He was never inclined to celebrate it openly inside the Rapids locker room or with friends after the game, but rather to subtly mark it as validation for the decision he made to come back to the game after admitting last fall he could no longer bear the fear of getting hit in the head again.

Pablo Mastroeni appeared in his 319th career regular season game last Saturday. He's eighth all-time in league history in appearances.

- USA TODAY Sports

The Rapids opened the season on the road in Dallas and succumbed in a 1-0 loss that was, during the course of a lengthy 34-game season, an entirely forgettable night in Frisco, Texas. But not for Mastroeni, who dutifully went about his business in his first start since March 18, 2012, and lasted the entire 90 minutes on the field, the first time he’s done that since Oct. 1, 2011.

In the process the 36-year-old midfielder became the first player in league history to appear in at least one game in 16 MLS seasons, further cementing his legacy among the iron men of the league. With his 319th regular-season game now in the books and No. 320 fast approaching in the Rapids’ home opener against the Philadelphia Union on Saturday (6 pm ET, MLS Live), Mastroeni is the only active player among the top 10 all-time leaders in games and minutes played, and if he plays two more healthy seasons in the league, he has a realistic shot of breaking both records.

But that, as Mastroeni will quickly admit, is way too presumptuous. He’s lived day to day for the better part of the past year-and-a-half when it comes to his career, which most people considered to be finished last spring. That’s when he stopped attending team practices because he’d grown to hate the game that made him a star. He disappeared into the comfort of his home or a neuropsychologist’s office. He meditated, he wrote in his journal and, when he was lucky, his mind let him sleep.

Last summer, a day like Saturday’s home opener was perhaps the farthest thing from his mind. Instead all Mastroeni wanted was peace and some kind of explanation for what was in his head, when the feeling would stop and, most strikingly for his future, who he would be if he could never play again.

“For any soccer player, you start playing at five years old and it becomes not even really so much what you do for a living anymore – it’s who you are,” he says. “And that’s all good until you don’t have it anymore. And then the question becomes: ‘Well, who the hell am I?’”

–-

There is nothing particularly noticeable about the play that threw Mastroeni’s career in doubt. No obvious intent. No malice. Just a simple foul called with no severe penalty for either player involved.

Rapids players hollered for some kind of punishment for hulking former Real Salt Lake defender Jámison Olave after he cracked heads with Mastroeni in a mid-air collision on Oct. 14, 2011, but, not surprisingly, none came. It’s a scene familiar to players in every soccer league in the world, and the result was typical: one man blinks, grimaces and walks away. The other struggles just to get to his feet again.

Mastroeni grimaces after sustaining a concussion during a match against Real Salt Lake on Oct. 14, 2011.

- USA TODAY Sports

The concussion was not the first of Mastroeni’s career. He recalls at least two during his younger days with the Miami Fusion, including one sustained after catching an errant elbow while leaping for a header. He was so disoriented he began crawling sideways towards the corner flag while the play continued behind him, but he only knows that because the trainer recounted the scene to him later.

Mastroeni never reported his symptoms, and, in an era when real concussion-safety awareness was still years off, he did what every other wide-eyed 20-something player did. He shook it off.

He thought for a time he’d shaken off the 2011 concussion, too, even though he didn’t play another minute that season. He missed the team’s abbreviated playoff run but returned to the club the next spring, and played 74 minutes of the team’s season-opening win over the Columbus Crew in March 2012.

But the night before the team’s second game – a road match against the Union – Mastroeni began to fade. Instead of eating with the team, he took his food to his hotel room, put the plates on his desk and went to sleep. He played 76 minutes the next day at PPL Park before he couldn’t take any more.

“At halftime of that game, I was getting cramps because I hadn’t trained all week, because I was dizzy and I didn’t feel right,” he says. “I was nauseous. I got goosebumps when I was running. All this crazy, crazy stuff.

“That night I couldn’t sleep, I felt sick, I had a headache,” he adds. “[The Rapids] gave me a few days off and I told them, ‘Hey guys, something’s not right with me, I need to figure this out.'”

What followed was a personal nightmare to which only the unlucky few can relate, and it lasted for months. Mastroeni battled all the typical concussion-related symptoms – sleep loss, nausea, sensitivity to light and noise, incessant headaches – and disappeared completely from the grounds at Dick’s Sporting Goods Park. He cut off communication at times with his teammates, too, and watched Rapids games from the comfort of his home, while his children wondered when he would be back on the TV.

Mastroeni spent three months waking up with blurred vision. He felt foggy, battled headaches and slept three hours a night. He couldn’t bear the intensity of the light at the grocery store. During the worst of it, he didn’t give a damn about playing one more minute of playing professional soccer.

“When you have a concussion, you just never think it’s going to end. And unfortunately for some people, it doesn’t end,” he says. “That was my fear, that it was continuously going to be like that for the rest of my life.”

In his mind, retirement from his playing career was the easiest and most sensible option. But he also entertained the idea of walking away from all aspects of the game, and perhaps finding something new to do with his life. He wanted, as he puts it, to disappear completely, and live in anonymity.

“It all kind of unraveled rather quickly,” Mastroeni says. “You don’t know who to blame, and of course, there is no one to blame. It’s a part of life and that’s what happens, but you want to blame someone because you’re so miserable. I didn’t know who to blame so I blamed the game, and that lasted a while.

WATCH: Mastroeni speaks with ColoradoRapids.com about his rehabilitation process and his decision to return to soccer.

“I wouldn’t go to the stadium,” he adds. “I was watching games at home, but I just couldn’t put myself in that environment, because then you start doing things with your heart, and not your brain. At that point, I didn’t really have either.”

READ: Rapids' Mastroeni emerging from "dark, dark place"

What helped usher him through the spring months and into the summer was the help of a Denver-area neuropsychologist, appointed to him as part of Major League Soccer’s concussion-awareness protocol. Mastroeni met with his doctor twice a week to work through the psychological aspects of the concussion, and he gradually adopted 45 minutes of daily meditation and one hour of daily journaling.

The journal entries paralleled his progress in the rehabilitation, and consequently opened with what he calls “some pretty dark stuff.” It was free-form, stream-of-consciousness writing mostly – what he’d eaten for lunch, interactions with his kids – that eventually became more structured children’s stories or introspective, satirical stories that cast Mastroeni as a troubled lead character.

“They were about how comical my life can be, given that it’s perceived from the outside that I have everything. But on the inside I’m just a roller coaster,” he says. “You live across the street from some people and they see you on the street: ‘Hey, how’s it going?’ Everything seems great. But we all have our demons to battle.

“It just helped me move forward instead of getting stuck in a rut or dwelling on it. The act of writing helped me release a lot of that pent-up emotion that was kind of stuck.”

Mastroeni still has the journals and shared some of them with his wife, but there’s really no need to let anyone else in. Who could really understand?

–-

Mastroeni didn’t return to the Rapids regularly until August, when a number of the physical symptoms of his concussion had receded and he could go through simple warm-ups with the team every other day. He progressed like that steadily, but at first went through the motions largely just to be back with his teammates. Actually playing in a game, he knew, was months away, if that moment would ever came at all.

What plagued Mastroeni was the psychological damage lingering in the months after the concussion, and what exactly was left of his identity. Considered one of the best American holding midfielders of his generation – he appeared in both the 2002 and 2006 World Cups – Mastroeni has long been considered one of Major League Soccer’s toughest and most unforgiving players. He’s the league’s all-time leader in yellow cards (80 total, 11 more than anyone else and roughly one earned every four games) and he’s committed 470 fouls in his career, just seven behind the league’s all-time leader, Jesse Marsch.

But the injury and the emotional "roller coaster" left him anxious, vulnerable, and, most damning for a man in his spot on the field, afraid. He didn’t want to disrupt the team by sporadically showing up at practice and then disappearing for weeks at a time. He didn’t want to be “the guy who’s so damn needy.”

And most importantly for his future, he could no longer play the way he’d always played.

“It became, ‘Do I even want to go into this tackle? Do I want to go for this head ball?’” he says. “I realized coming back that my M.O. was about dying on the field, about battling, about going through tackles, getting head balls and getting beat up.

“If I can’t do that, I can’t play this game.”

Mastroeni celebrates scoring a goal in the 2010 Eastern Conference semifinals against the Columbus Crew.

- USA TODAY Sports

The club, meanwhile, let Mastroeni heal at his own pace throughout the process, and even tried to take the moment in stride when he walked into technical director Paul Bravo’s office during the summer and told him he was quitting. Petrified by the thought of another concussion and more months spent in a darkened room, Mastroeni told Bravo, “I’m done, man. I can’t do this anymore.”

Bravo swallowed the news and offered up anything he could to keep Mastroeni in the fold. Having played for Colorado himself from 1997-2001, Bravo knew the club’s history and what Mastroeni had brought to Denver over the course of 11 rugged seasons, so he let Mastroeni take his pick: assistant coach, club ambassador, a spot in the front office, anything.

"He had earned the right to write his own script,” Bravo says.

But as Mastroeni continued to work out with his teammates even in a limited capacity, something changed. He reversed his course on retirement in the fall perhaps because he couldn't honestly conceive spending his days without soccer, or he simply wanted to compete again.

"He still had that fire in him," said former New England Revolution star and concussion-awareness advocate Taylor Twellman, who counseled Mastroeni last year. "We'd been talking about everything through the process, and suddenly I got a quick text from him that said, 'Dude, I think I finally turned a corner.'"

Mastroeni gradually eased back into a regular routine of workouts with the team, slowly building up both his stamina and his confidence. Eventually he was stable enough to not only play in short-sided scrimmages, but also head balls during the flow of the game. He cut his daily meditation down to 25 minutes while he spent the other 20 at night reading with his children. He told his wife he was going back, and they faced the future together.

READ: Mastroeni embraces new "half-coach role," mulls future

Life inched toward normalcy, and he approached Bravo with the news that he would indeed return to the club in 2013, if they would have him.

“When he did finally come back and he was in the group, you could see in his eyes, his approach was much different,” Bravo says. “You could hear it in the way he spoke. He had the spark. As a matter of fact, I kind of expected it. I was always optimistic that he would return; it was like getting a new player.”

–-

The obvious question remains, however, as to why Mastroeni would even be allowed back on the field after such a traumatic injury. Similar concussions have famously ended the luminous careers of MLS star players like Twellman, Alecko Eskandarian and Jimmy Conrad, and cut short the playing days of countless others. Mastroeni’s symptoms dovetailed theirs, yet he was still cleared to play before the 2012 game in Philadelphia and again earlier this year.

Dr. Ruben Echemendia, the Pennsylvania-based clinical neuropsychologist who serves as the Chair of Major League Soccer’s nine-person Concussion Committee and also works on concussion protocols for the NHL and the US Soccer Federation, said that although the symptoms Mastroeni experienced after the 2011 concussion were common for such an injury, he would never have been cleared to play had he not passed the league’s methodical sequence of tests for all players dealing with brain injuries.

The testing process begins for every player when he joins the league and goes through a computerized baselining test to assess cognitive function and brain activity. After the player suffers a brain injury, he’s referred to his club’s assigned neuropsychologist to asses his cognitive function, and when he’s symptom-free while at rest, he’s once again put through the same baseline test and a battery of traditional pencil-and-paper neuropsychology tests to compare the results.

Major League Soccer

Concussion Protcol

Each player is administered a computerized baseline test to assess cognitive function and brain activity upon entering the league, but after suffering a concussion, they must pass the following series of tests without symptoms in order to return to competition.

A re-test of the computerized baseline exam and a battery of traditional pencil-and-paper neuropsychology tests

Graded physical progression, including stationary bike or elliptical machine performed at a low level

* Interval training and sprints, including the beep test

Non-contact soccer drills

Weight training

Controlled contact on the field, including jostling with teammates

Heading progressions from six up to 20 yards

*Controlled full contact in instrasquad scrimmage

- MLS Concussion Committee

Among those tasks are learning and remembering a new list of words, recalling certain designs or reciting a given sequence of numbers forward and backward. If the computer gives a player 16 words, for example, how many can he remember the first time? The second time? The fifth? The test focuses on reaction time and how quickly he can process information.

In Mastroeni’s case, the baseline test administered in the days immediately following the 2011 concussion stopped him dead in his tracks. Although he remembers nothing of the incident itself or much of the three days that followed, he clearly remembers taking the test, walking out of the medical office and calling Rapids head trainer Jaime Rojas on the drive home to tell him that even though he didn’t quite feel right physically, he had easily passed the baseline exam.

“Pablo,” Rojas told him after getting the results a few hours later, “you failed in every category possible.”

Mastroeni eventually passed the cognitive tests, however, and then faced a series of graded physical progression tests, starting with activities like a stationary bike or elliptical machine for 15 minutes at a low level. When he showed no signs of symptoms as his heart rate climbed, he moved to interval training and sprints.

Then came non-contact soccer drills, followed by strength training, and eventually controlled contact on the field. When Mastroeni could handle these tasks and then jostling with his former teammates without symptoms, he moved to a series of heading progressions: Balls thrown from six yards from each side increasing to a distance of 10 yards, and then 20.

Mastroeni struggled with the final heading stage before eventually clearing it near the end of the regular season last fall, but his real problem wasn’t physical. His symptoms at that point were entirely psychological, and a product of already medically diagnosed anxiety problems. He couldn’t bear the thought of really heading the ball when it counted, and his confidence was still lacking. It's an expected consequence, says Echemendia.

“Now a player is worrying about, ‘What’s happening to me? What’s going on? How am I doing and how are people going to view me now?’” Echemendia says. “That creates a whole cycle of anxiety and depression, and all of that is very common with concussions.”

Mastroeni (right) andColorado Rapids defender Diego Calderon during the 2013 preseason.

- Courtesy of ColoradoRapids.com

Added to that problem was a set of emotions Mastroeni felt and any concussion patient would feel after gradually returning to their everyday lives: Am I experiencing this headache, this nausea, this light-headedness because of the concussion, or just because every human feels this at some point on any given day?

“When do you decide if it’s normal vs. abnormal?” Echemendia says. “That’s the toughest part in coming back. Anyone who’s had a concussion tends to look at life through the lens of concussion and interpret what they’re experiencing with the thought, ‘Oh, my concussion must have caused this.’”

“It’s a process,” he adds. “A light doesn’t come on one day and say, ‘OK, it’s all done.’”

Mastroeni was cleared for the penultimate step of the rehabilitation process – controlled full contact in an intrasquad scrimmage – last fall, but the season was long gone by then. He trained with the club in 90-minute sessions in November first with a soft helmet and then without before he realized that he was ready to return when preseason opened in January.

“When it got to the point when it was all involuntary like it’s always been,” he says, “it was like, ‘Damn man, you’re ready to go.’”

–-

Not surprisingly, Mastroeni’s return didn’t go unnoticed by Rapids fans when preseason camp opened in January. One fan in particular, a fifth-grade student attending school in Dacono, Colo., sent Mastroeni a letter and a detailed 25-page science experiment examining the positive effect a soft helmet can have on acute blows to the head.

Mastroeni examined the paper and promptly wrote a letter back to the young scientist, and they’ve remained in touch ever since. Mastroeni wore a soft helmet for the Rapids’ first game during the preseason in Arizona but hasn’t since, and despite his wish to see players wear helmets at the youth level, he can’t bring himself to wear one as a professional.

Mastroeni wore a soft helmet briefly during the preseason this year, but he says he won't wear one during the regular season.

- USA TODAY Sports

“Any time you see a guy wearing a helmet in soccer, there’s still doubt in his mind, or else he wouldn’t wear a helmet,” Mastroeni says. “There’s a battle with the idea that I can’t go out there and be worried about taking that blow. I have to be focused on what I’m doing out there.

“Wearing a helmet just wasn’t going to be a possibility, having had so much fear last year about getting hit in the head again. I’d never be confronting the problem.”

READ: Pareja names Mastroeni as Rapids captain in 2013

How much of that is bravado, and how much of Mastroeni’s return is fueled simply by an athlete’s pride? It’s tough for outsiders to speculate, and impossible to question how any player deals with his own rehabilitation. Critics will wonder why he would risk another serious injury when he has a family to consider, and his supporters can point to his perseverance as a shining example of how to overcome frightening adversity.

For an athlete who’s accomplished as much as Mastroeni has – an MLS Best XI selection with Miami in 2001, an MLS Cup with Colorado in 2010, a US national team career with 68 caps and two World Cup appearance – the motivation appears to be the drive to continue competing at any cost, or perhaps the fear of letting that feeling fade if his playing career comes to an end.

WATCH: Mastroeni speaks with ColoradoRapids.com after the team's first preseason game in Arizona.

“You can’t say Pablo shouldn’t do this, because every situation is different,” says Twellman, who founded the nonprofit Think Taylor after he retired in 2010. “It’s the rush. For Pablo, I don’t think he wanted his last year to go the way it went.”

For his part, Mastroeni is fully aware of critics who might ridicule him for putting soccer in front of his safety, thereby potentially affecting the quality of life for his family. He wrestled with that much of last year, knowing he was dealing with a completely different set of emotions as a husband and father than when he was a young player solely focused on his career.

But now it’s forward, the only way Mastroeni wants to go. It’s the only way to try and rediscover some of the man he was before this began.

“This is the last step of my recovery,” he insists. “Getting back out there and overcoming my fears … being with the guys again. I want to feel a sense of normalcy again, and I want to feel like I belong.”